OPINION: Why I hope the stats are right about Swedish children's reading and maths

Richard Orange finds the slow progress his children are making at their Swedish municipal school excruciating, particularly the handwriting. But the statistics indicate that, at least when it comes to reading, maths, and science, they should catch up by around the age of 11.

Handwriting has been the hardest thing about sending my children to the local Swedish municipal school in Malmö.

My two children's handwriting is worse than that of their 5-year-old English cousins, who already writes in childish joined-up letters, while they at age 9 and 11 still sometimes gets their 'b's and 'd's mixed up.

"You can write them any way you want," my daughter complains if I try to get her to start her letters at the top rather than in her own idiosyncratic way, and her teachers confirm that this is indeed the instructions she's been given.

One even confessed to me that it was a policy she didn't herself agree with, but she had no choice.

The fact that I'm trying to make my daughter do something her teachers have told her doesn't matter, however, means I've found it impossible to motivate them to practise handwriting at home.

I'm worried that they will never be able to take notes rapidly by hand, which while clearly not life-ending, is, I think, a bit limiting.

Year six students use their computers in a school in Stockholm. Photo: Alexander Olivera/TT

Paulina Neuding, the Svenska Dagbladet columnist, last year published a series of articles here, here and here comparing the lamentable level of handwriting in Swedish schools with that of pupils in Belgium, Poland, and Germany, referring to research indicating that writing by hand activates the brain and memory in a way writing on a laptop does not.

Neuding stresses that parents should not simply be concerned about their children having nice handwriting or not, but about whether they will be able to write by hand at all.

"It's important for parents to recognise that handwriting is de-prioritised to such an extent that it isn't at all certain that your child will learn to write properly at school," she wrote in her first article on the topic.

Ulf Frederiksson, the professor at Stockholm University responsible for the reading comprehension part of the Pisa study, tells me she may be right.

"There is no international comparison on handwriting, but it's probably true that Swedish schools have had less emphasis on formal handwriting over the last 20 to 30 years," he said.

"It hasn't really had a big impact on students' reading skills. But if you did do a comparative study of handwriting legibility in different countries, Swedish students would probably come out rather poorly."

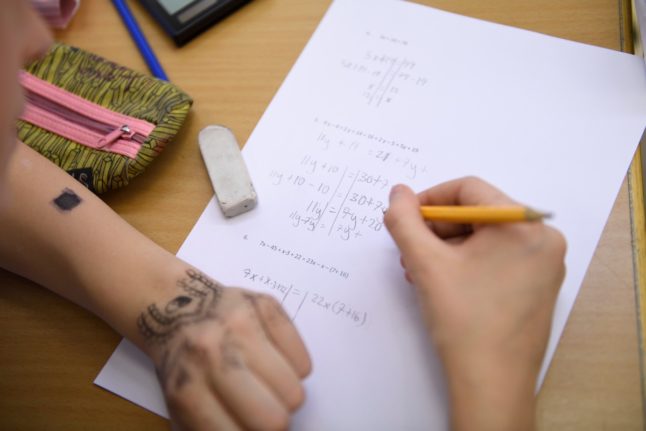

Swedish year four students are slightly behind the EU/OECD average. Photo: Gorm Kallestad/NTB/TT

I've also struggled with the fact children start school a year later in Sweden than in my home country. And as the first year of school – the zero class or nollan – is pretty much a continuation of kindergarten, you could argue that they start off two years behind.

Frederiksson said that all the Nordic countries have traditionally started school a year later than the rest of Europe, something he puts down to low population density which meant that students would have had to walk a long way to their village school, something that they would not have been able to do until they were seven.

I've found the slow start agonising, but the statistics do seem to suggest that by the time they are about 11, pupils in Sweden aren't actually much behind their counterparts in the UK, France or Germany.

In the Pirls study published on Tuesday, Swedish pupils aged around 11 did better than the EU/OECD average in reading comprehension, a little behind those in England and Finland but ahead of those in France, Germany, Denmark and Norway.

If you strip out students who do not speak Swedish at home, Swedish students actually had the highest reading ability of any country.

Swedish 11-year-old pupils were also above the EU/OECD average in science, according to the most recent survey from 2019, neck and neck with England, but above students in Germany and France.

When it comes to maths, Swedish year four pupils were a little behind the EU/OECD average in the most recent 2019 study, behind England, but at the same level as Germany and better than France.

Swedish schools are not that far behind when it comes to maths. Photo: Henrik Montgomery/TT

I very much hope these statistics are right, as I've been quite alarmed that my children's school seems to avoid anything that requires drilling or memorisation – the times tables, national capital cities, location of countries, important dates.

My children do not seem to be learning what their UK counterparts learn, or at least what I did. But perhaps missing out these more mundane exercises means that children feel more positively towards schools, helping the acquisition of knowledge in other areas.

I do feel that now my daughter is in the fourth class, the pace is picking up, with more homework and more challenging tasks. But, to my frustration, the time for working on her handwriting appears to be over.

Frederiksson remembers that when he was training to be a primary school teacher in the 1970s, teaching handwriting was still seen as important. But that this ceased to be the case quite early in his career.

Anna Nordlund, an assistant professor at Uppsala University focused on the role of children's literature in teaching, dates the downgrading of handwriting to the 1994 curriculum.

"Younger teachers and student teachers today did not have any systematic education in how to write by hand when they, themselves, were at school," she said. "I have taught student teachers who were not able to read children's picture books printed in handwriting, such as the Tove Jansson classic Who Will Comfort Toffle?".

She said she frequently encountered student teachers who are themselves unable to take notes with a pen and paper, and explained that there is little if anything in the current Swedish teaching methodology they study that covers handwriting.

"Since the 2000s, there hasn't been any requirement in teacher education for students to receive instruction in handwriting methodology, which used to be an important part of the education to be a primary school teacher," she said.

The Swedish curriculum today requires students in years 1-4 to be able to write "simple texts with legible handwriting", but as there is no detail on how this should be done or how to define "legible", Frederiksson says it is in practice almost entirely up to the teacher how and to what level they want to teach handwriting.

While a few teachers still teach cursive, others more or less go straight to laptops, bypassing handwriting altogether.

"Teachers have a certain degree of freedom on how to teach it, so some teachers may spend more time on it and others are not really giving any kind of handwriting instruction, because they think the children should get directly to using computers," he said.

"That has been fairly much disputed, because there is research suggesting that if children learn to write by hand, it makes it easier to remember the shapes of the letters."

With Neuding's handwriting campaign and schools minister Lotta Edholm last spring dramatically scrapping the Swedish National Agency for Education's digitalisation strategy, it feels like the tide is turning in Sweden.

Unfortunately it will be too late for my two children. But perhaps I can take comfort in the statistics which show that while their handwriting is likely to be much poorer than their cousins back home, they will be at least not be too behind on maths, reading and science.

Comments (1)

See Also

Handwriting has been the hardest thing about sending my children to the local Swedish municipal school in Malmö.

My two children's handwriting is worse than that of their 5-year-old English cousins, who already writes in childish joined-up letters, while they at age 9 and 11 still sometimes gets their 'b's and 'd's mixed up.

"You can write them any way you want," my daughter complains if I try to get her to start her letters at the top rather than in her own idiosyncratic way, and her teachers confirm that this is indeed the instructions she's been given.

One even confessed to me that it was a policy she didn't herself agree with, but she had no choice.

The fact that I'm trying to make my daughter do something her teachers have told her doesn't matter, however, means I've found it impossible to motivate them to practise handwriting at home.

I'm worried that they will never be able to take notes rapidly by hand, which while clearly not life-ending, is, I think, a bit limiting.

Paulina Neuding, the Svenska Dagbladet columnist, last year published a series of articles here, here and here comparing the lamentable level of handwriting in Swedish schools with that of pupils in Belgium, Poland, and Germany, referring to research indicating that writing by hand activates the brain and memory in a way writing on a laptop does not.

Neuding stresses that parents should not simply be concerned about their children having nice handwriting or not, but about whether they will be able to write by hand at all.

"It's important for parents to recognise that handwriting is de-prioritised to such an extent that it isn't at all certain that your child will learn to write properly at school," she wrote in her first article on the topic.

Ulf Frederiksson, the professor at Stockholm University responsible for the reading comprehension part of the Pisa study, tells me she may be right.

"There is no international comparison on handwriting, but it's probably true that Swedish schools have had less emphasis on formal handwriting over the last 20 to 30 years," he said.

"It hasn't really had a big impact on students' reading skills. But if you did do a comparative study of handwriting legibility in different countries, Swedish students would probably come out rather poorly."

I've also struggled with the fact children start school a year later in Sweden than in my home country. And as the first year of school – the zero class or nollan – is pretty much a continuation of kindergarten, you could argue that they start off two years behind.

Frederiksson said that all the Nordic countries have traditionally started school a year later than the rest of Europe, something he puts down to low population density which meant that students would have had to walk a long way to their village school, something that they would not have been able to do until they were seven.

I've found the slow start agonising, but the statistics do seem to suggest that by the time they are about 11, pupils in Sweden aren't actually much behind their counterparts in the UK, France or Germany.

In the Pirls study published on Tuesday, Swedish pupils aged around 11 did better than the EU/OECD average in reading comprehension, a little behind those in England and Finland but ahead of those in France, Germany, Denmark and Norway.

If you strip out students who do not speak Swedish at home, Swedish students actually had the highest reading ability of any country.

Swedish 11-year-old pupils were also above the EU/OECD average in science, according to the most recent survey from 2019, neck and neck with England, but above students in Germany and France.

When it comes to maths, Swedish year four pupils were a little behind the EU/OECD average in the most recent 2019 study, behind England, but at the same level as Germany and better than France.

I very much hope these statistics are right, as I've been quite alarmed that my children's school seems to avoid anything that requires drilling or memorisation – the times tables, national capital cities, location of countries, important dates.

My children do not seem to be learning what their UK counterparts learn, or at least what I did. But perhaps missing out these more mundane exercises means that children feel more positively towards schools, helping the acquisition of knowledge in other areas.

I do feel that now my daughter is in the fourth class, the pace is picking up, with more homework and more challenging tasks. But, to my frustration, the time for working on her handwriting appears to be over.

Frederiksson remembers that when he was training to be a primary school teacher in the 1970s, teaching handwriting was still seen as important. But that this ceased to be the case quite early in his career.

Anna Nordlund, an assistant professor at Uppsala University focused on the role of children's literature in teaching, dates the downgrading of handwriting to the 1994 curriculum.

"Younger teachers and student teachers today did not have any systematic education in how to write by hand when they, themselves, were at school," she said. "I have taught student teachers who were not able to read children's picture books printed in handwriting, such as the Tove Jansson classic Who Will Comfort Toffle?".

She said she frequently encountered student teachers who are themselves unable to take notes with a pen and paper, and explained that there is little if anything in the current Swedish teaching methodology they study that covers handwriting.

"Since the 2000s, there hasn't been any requirement in teacher education for students to receive instruction in handwriting methodology, which used to be an important part of the education to be a primary school teacher," she said.

The Swedish curriculum today requires students in years 1-4 to be able to write "simple texts with legible handwriting", but as there is no detail on how this should be done or how to define "legible", Frederiksson says it is in practice almost entirely up to the teacher how and to what level they want to teach handwriting.

While a few teachers still teach cursive, others more or less go straight to laptops, bypassing handwriting altogether.

"Teachers have a certain degree of freedom on how to teach it, so some teachers may spend more time on it and others are not really giving any kind of handwriting instruction, because they think the children should get directly to using computers," he said.

"That has been fairly much disputed, because there is research suggesting that if children learn to write by hand, it makes it easier to remember the shapes of the letters."

With Neuding's handwriting campaign and schools minister Lotta Edholm last spring dramatically scrapping the Swedish National Agency for Education's digitalisation strategy, it feels like the tide is turning in Sweden.

Unfortunately it will be too late for my two children. But perhaps I can take comfort in the statistics which show that while their handwriting is likely to be much poorer than their cousins back home, they will be at least not be too behind on maths, reading and science.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.