ANALYSIS: Macron's unrequited love affair with Africa

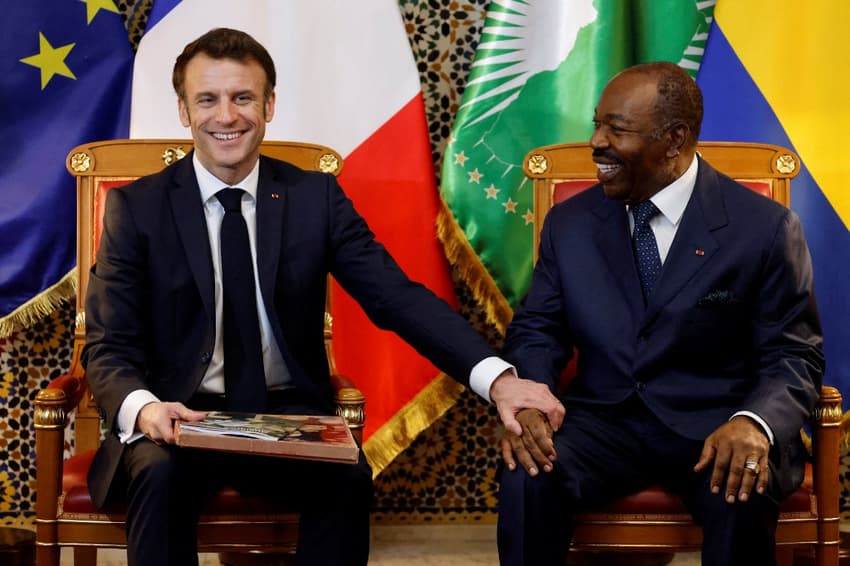

As French president Emmanuel Macron embarks on another trip to countries in Africa, John Lichfield looks at why French-African relations are at such a low, despite unprecedented efforts from Paris.

President Emmanuel Macron has a deep affection for and obsession with Africa. Friends say that the love affair began when he was an intern in the French embassy in Nigeria in 2002.

He was sent there by the French, political finishing school, ENA (Ecole Nationale d’Administration). Macron has since abolished ENA but he is constantly drawn back to Africa.

On Wednesday he began a five-day swing through four African countries. This is his 18th visit to the continent in less than six years as President - roughly one visit for every four months.

There is a great Macronian paradox here - one of many. The President has expended more time and energy than any of his predecessors into trying to rebuild France’s relationship with Africa and especially with the former French colonies.

And yet the French presence in Africa has never been so rejected. France’s right to a special role in Africa is now contested both by the continent’s selfish political elites and by the tens of millions of young Africans who aspire to better governments and better lives.

France has been all but booted out of Mali and Central Africa, It is in the process of being ejected from Burkina Faso. Something similar is happening in Niger and Chad.

Even in the big, former West African colonies like Senegal and Ivory Coast, French political and cultural influence is increasingly rejected or despised.

In part, but only in part, this is the work of Russian propaganda. The Russia Today TV channel and Sputnik news agency have an enormous following in all Francophone central and west Africa countries.

They seed conspiracy theories about persistent French “colonial” interference. They work in de facto alliance with the Wagner mercenary army, run on the Kremlin’s behalf by the billionaire oligarch (the crook and former cook) Yevgeny Prigozhin.

The Wagner army has already replaced the French military as the foreign gendarme in Mali, Central Africa and Burkina Faso. It has been implicated in massacres of civilians and the seizure of gold and diamonds.

Bizarrely, anti-French propaganda in Africa is now also being spread by Hollywood. In the latest film in the Wakanda series (Wakanda Forever), set in a fictional, never-colonised African country, the 'baddies' are the French army. The world outside Wakanda is dominated by two empires, American (quite bad) and French (very bad indeed).

But the unholy and unthinking alliance between Hollywood and the Kremlin is not solely responsible for the surge in anti-French feeling in Africa. It merely exploits and deepens it.

An unhealthy and corrupt relationship existed until the 1990s between Paris and political and economic elites in France’s former African colonies. This system – known as Françafrique – was partially, but not entirely, dismantled by Macron’s predecessors.

The often clumsy French efforts to fight corruption and foster democracy (while preserving French economic interests) mean that France is now resented by both elites and masses. Something similar is true of France’s military efforts to contain Islamist insurgents in the Sahel. The rebels have come to be seen (wrongly) as more insurgent than Islamist.

In sum, the elites detest French efforts to restrain their power. The masses see that the elites remain in power and blame the French.

Macron has taken several important steps to try to create a new relationship to replace Françafrique. In a speech in Ouagadougou in 2017, he said France no longer had a self-interested Africa policy. There would, he said, be a “new partnership”.

He has since started the process of returning an extraordinary treasury of African art looted in colonial times and held in French museums. France will soon return to Ivory Coast the “tambour parleur” (talking drum), a three-metres long, wooden, man-crocodile capable of sending messages for 30 kilometres. It was stolen in 2016.

Macron also says that he is ready to end French involvement in the so-called “African franc” or CFA, a shared currency (or actually two regional currencies), which is tied to the Euro and guaranteed by Paris. The CFA is largely beneficial to its member countries. It has, nonetheless, become one of the most fertile sources of the lurid, anti-French conspiracy theories which circulate in Africa.

Before he set out for Gabon, the two Congo’s and Angola, Macron made a speech in which he renewed his 2017 promise. He announced that the remaining French military bases on the continent would be placed under shared control. He outlined a new legal framework to hasten the return of stolen artefacts.

It is telling, however, that Macron spoke in advance to avoid having to say much while on the road. The four countries he is visiting are among the most autocratic in Africa.

The visit will, as Le Monde pointed out, plunge Macron into the “heart of the contradictions” of his Africa policy. He knows that he must avoid lecturing political elites on democracy. And yet, if he fails to do so, how can he persuade young Africans that France is on the side of change?

“Whatever we do it will never be enough and often misinterpreted,” said one presidential adviser wearily.

Achille Mbempe, the Camerounian political scientist and adviser to Macron, says that a long and difficult road lies ahead. He told the magazine, Le Point: “The president wants a dialogue but the Africans refuse because they fear they will be manipulated. They say Macron is insincere but they offer no alternative. Do they prefer military coup d’etats? Jihadist violence? Third terms of office? Sons succeeding fathers?”.’

Macron can always look forward to his return on Sunday to the comparative simplicities of French politics and pension reform.

Comments

See Also

President Emmanuel Macron has a deep affection for and obsession with Africa. Friends say that the love affair began when he was an intern in the French embassy in Nigeria in 2002.

He was sent there by the French, political finishing school, ENA (Ecole Nationale d’Administration). Macron has since abolished ENA but he is constantly drawn back to Africa.

On Wednesday he began a five-day swing through four African countries. This is his 18th visit to the continent in less than six years as President - roughly one visit for every four months.

There is a great Macronian paradox here - one of many. The President has expended more time and energy than any of his predecessors into trying to rebuild France’s relationship with Africa and especially with the former French colonies.

And yet the French presence in Africa has never been so rejected. France’s right to a special role in Africa is now contested both by the continent’s selfish political elites and by the tens of millions of young Africans who aspire to better governments and better lives.

France has been all but booted out of Mali and Central Africa, It is in the process of being ejected from Burkina Faso. Something similar is happening in Niger and Chad.

Even in the big, former West African colonies like Senegal and Ivory Coast, French political and cultural influence is increasingly rejected or despised.

In part, but only in part, this is the work of Russian propaganda. The Russia Today TV channel and Sputnik news agency have an enormous following in all Francophone central and west Africa countries.

They seed conspiracy theories about persistent French “colonial” interference. They work in de facto alliance with the Wagner mercenary army, run on the Kremlin’s behalf by the billionaire oligarch (the crook and former cook) Yevgeny Prigozhin.

The Wagner army has already replaced the French military as the foreign gendarme in Mali, Central Africa and Burkina Faso. It has been implicated in massacres of civilians and the seizure of gold and diamonds.

Bizarrely, anti-French propaganda in Africa is now also being spread by Hollywood. In the latest film in the Wakanda series (Wakanda Forever), set in a fictional, never-colonised African country, the 'baddies' are the French army. The world outside Wakanda is dominated by two empires, American (quite bad) and French (very bad indeed).

But the unholy and unthinking alliance between Hollywood and the Kremlin is not solely responsible for the surge in anti-French feeling in Africa. It merely exploits and deepens it.

An unhealthy and corrupt relationship existed until the 1990s between Paris and political and economic elites in France’s former African colonies. This system – known as Françafrique – was partially, but not entirely, dismantled by Macron’s predecessors.

The often clumsy French efforts to fight corruption and foster democracy (while preserving French economic interests) mean that France is now resented by both elites and masses. Something similar is true of France’s military efforts to contain Islamist insurgents in the Sahel. The rebels have come to be seen (wrongly) as more insurgent than Islamist.

In sum, the elites detest French efforts to restrain their power. The masses see that the elites remain in power and blame the French.

Macron has taken several important steps to try to create a new relationship to replace Françafrique. In a speech in Ouagadougou in 2017, he said France no longer had a self-interested Africa policy. There would, he said, be a “new partnership”.

He has since started the process of returning an extraordinary treasury of African art looted in colonial times and held in French museums. France will soon return to Ivory Coast the “tambour parleur” (talking drum), a three-metres long, wooden, man-crocodile capable of sending messages for 30 kilometres. It was stolen in 2016.

Macron also says that he is ready to end French involvement in the so-called “African franc” or CFA, a shared currency (or actually two regional currencies), which is tied to the Euro and guaranteed by Paris. The CFA is largely beneficial to its member countries. It has, nonetheless, become one of the most fertile sources of the lurid, anti-French conspiracy theories which circulate in Africa.

Before he set out for Gabon, the two Congo’s and Angola, Macron made a speech in which he renewed his 2017 promise. He announced that the remaining French military bases on the continent would be placed under shared control. He outlined a new legal framework to hasten the return of stolen artefacts.

It is telling, however, that Macron spoke in advance to avoid having to say much while on the road. The four countries he is visiting are among the most autocratic in Africa.

The visit will, as Le Monde pointed out, plunge Macron into the “heart of the contradictions” of his Africa policy. He knows that he must avoid lecturing political elites on democracy. And yet, if he fails to do so, how can he persuade young Africans that France is on the side of change?

“Whatever we do it will never be enough and often misinterpreted,” said one presidential adviser wearily.

Achille Mbempe, the Camerounian political scientist and adviser to Macron, says that a long and difficult road lies ahead. He told the magazine, Le Point: “The president wants a dialogue but the Africans refuse because they fear they will be manipulated. They say Macron is insincere but they offer no alternative. Do they prefer military coup d’etats? Jihadist violence? Third terms of office? Sons succeeding fathers?”.’

Macron can always look forward to his return on Sunday to the comparative simplicities of French politics and pension reform.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.