Income inequality in Sweden higher than at any time in nearly 50 years

Income inequality in Sweden rose sharply in 2021, hitting the highest level since records began nearly 50 years ago, according to a report from the country's statistics agency.

According to Statistics Sweden's latest income report, Sweden's Gini-coefficient rose from 0.31 in 2020 to 0.34 in 2021, overtaking the levels seen in the run-up to the 2007 global financial crisis, and higher than at time since the agency started tracking income inequality in 1975. The Gini coefficient starts at 0 for perfect equality and rises to 1 in the most unequal distribution of incomes possible.

"This means that incomes in Sweden have not been divided so unequally since at least 1975," said Johan Lindberg, one of the statisticians behind the report, said in a press release.

Here's Statistics Sweden's table showing the Gini-coefficient for economic standard, with the light blue line excluding capital gains, and the red excluding all gains from capital investments.

The Gini coefficient for economic standard. Photo: Statistics Sweden

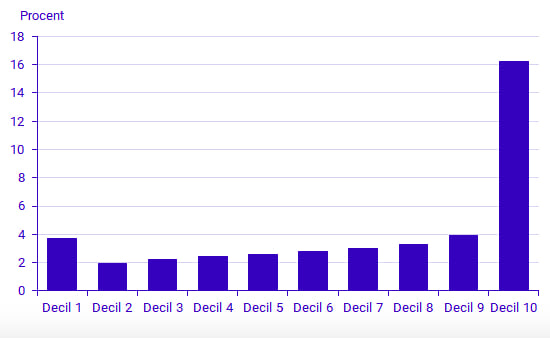

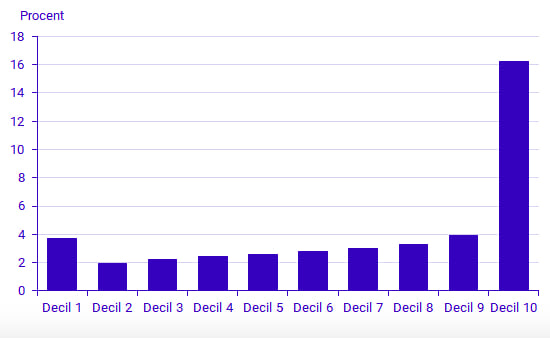

The sharp rise in income inequality in 2021 came mainly because the incomes of the top 10 percent of households in Sweden rose in 2021 by over 16 percent, compared to less than 4 percent for each of the bottom nine deciles of Swedish households.

"The decile of the population with the highest incomes saw their incomes rise significantly more than the rest of the population during 2021," Lindberg said.

Here's Statistics Sweden's chart showing how incomes increased in 2021 in the various deciles of earners.

Photo: Statistics Sweden

Daniel Waldenström, an economics professor based at Sweden's Research Institute for Industrial Economics, said that the sharp jump in income for the most well-off could be explained mainly by them selling shares, property, and other assets after the exceptional rises in prices that year.

"These are incomes of a one-off nature," he told the TT newswire, arguing that the rise was more "a manifestation of differences which already existed", rather than a genuine increase in real inequality. "If you take a broad-brush view, inequality in Sweden hasn't risen that much for 10-15 years."

He said that Sweden had seen the sharpest rise in inequality during the Swedish Financial Crisis in the 1990s.

"It was an extreme situation then, with high unemployment, low economic growth, and a bad economy," he said.

And here's the Gini-coefficient going back to 1975, using three different ways of measuring it.

The Gini-coefficient as measured since 1975. Source: Statistics Sweden

Mikael Damberg, who was finance minister in 2021, told TT that the rise in inequality in 2021 was not the result of any political decisions, and was likely to be reversed in 2023, as share prices and property prices fall.

"On paper, it's going to look like a great year for equality, but at the same time, we're seeing reports that schoolchildren are eating more food at school and families are seeing help from charities," he said.

Although economic inequality increased in 2021, even poorer people in Sweden were better off, with the median economic standard after inflation rising by 2.7 percent compared to 2020, something Lindberg said was "the greatest rise between two years since 2015".

Comments

See Also

According to Statistics Sweden's latest income report, Sweden's Gini-coefficient rose from 0.31 in 2020 to 0.34 in 2021, overtaking the levels seen in the run-up to the 2007 global financial crisis, and higher than at time since the agency started tracking income inequality in 1975. The Gini coefficient starts at 0 for perfect equality and rises to 1 in the most unequal distribution of incomes possible.

"This means that incomes in Sweden have not been divided so unequally since at least 1975," said Johan Lindberg, one of the statisticians behind the report, said in a press release.

Here's Statistics Sweden's table showing the Gini-coefficient for economic standard, with the light blue line excluding capital gains, and the red excluding all gains from capital investments.

The sharp rise in income inequality in 2021 came mainly because the incomes of the top 10 percent of households in Sweden rose in 2021 by over 16 percent, compared to less than 4 percent for each of the bottom nine deciles of Swedish households.

"The decile of the population with the highest incomes saw their incomes rise significantly more than the rest of the population during 2021," Lindberg said.

Here's Statistics Sweden's chart showing how incomes increased in 2021 in the various deciles of earners.

Daniel Waldenström, an economics professor based at Sweden's Research Institute for Industrial Economics, said that the sharp jump in income for the most well-off could be explained mainly by them selling shares, property, and other assets after the exceptional rises in prices that year.

"These are incomes of a one-off nature," he told the TT newswire, arguing that the rise was more "a manifestation of differences which already existed", rather than a genuine increase in real inequality. "If you take a broad-brush view, inequality in Sweden hasn't risen that much for 10-15 years."

He said that Sweden had seen the sharpest rise in inequality during the Swedish Financial Crisis in the 1990s.

"It was an extreme situation then, with high unemployment, low economic growth, and a bad economy," he said.

And here's the Gini-coefficient going back to 1975, using three different ways of measuring it.

Mikael Damberg, who was finance minister in 2021, told TT that the rise in inequality in 2021 was not the result of any political decisions, and was likely to be reversed in 2023, as share prices and property prices fall.

Although economic inequality increased in 2021, even poorer people in Sweden were better off, with the median economic standard after inflation rising by 2.7 percent compared to 2020, something Lindberg said was "the greatest rise between two years since 2015".

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.