Descendants of International Brigades to get fast-track Spanish nationality

Spain will give the descendants of International Brigade fighters who fought fascism during the Civil War an expressway to Spanish citizenship and dual nationality, with people from the UK, the US and many other countries eligible.

Descendants

The children and grandchildren of fighters who fought for the International Brigades during Spain’s Civil War will be able to acquire Spanish citizenship - and won’t have to give up their other nationality in order to do so.

The fighters themselves have been able to apply for Spanish citizenship since 1996, though they were required to drop their other nationality. Spain’s 2007 Historical Memory Law removed that requirement, though the offer of citizenship was not extended to their descendants.

There was confusion in 2020 when Spain's then deputy Prime Minister Pablo Iglesias tweeted that descendants of International Brigade fighters would be included in legislation, but when the final legal text appeared, it confirmed that the proposal did not stretch to descendants and only included the International Brigade veterans themselves.

Now Spain's new Democratic Memory Law, which passed the Spanish Senate on October 5th and officially became law on October 21st, finally extends the citizenship offer to descendants who can get Spanish nationality without losing theirs.

They will even be able to do it through the fast-tracked naturalisation process - seen as the expressway to Spanish citizenship and used by public figures such as Barcelona footballer Ansu Fati and actress Imperio Argentina.

READ ALSO:

- What are the other ways foreigners can get fast-track Spanish citizenship?

- Do you really have to give up your original nationality to become Spanish?

According to the Asociación de Amigos de las Brigadas Internacionales (AABI), a group involved with drafts of the legislation, there are at least one hundred known descendants that have been identified so far. They come from around the world, including France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Cuba, the former Yugoslavia, Argentina, Canada, Australia, and the United States.

As there are so few descendants of international brigade fighters, however, many view their inclusion in the citizenship legislation as a symbolic gesture that is part of the Democratic Memory Law's efforts to settle historical debts with the past.

Though the legislation does extend citizenship, it's not thought that a flood of applications will follow. "There will be no avalanche, it is a symbolic measure that has a purely sentimental importance for the relatives of the fighters," the AABI explained to Spanish news website Newtral.es.

Participants wave republican flags during a 2015 march called by the Friends of International Brigades Association to commemorate the involvement of the International Brigades in the Battle of Jarama during the Spanish Civil War. (Photo by CURTO DE LA TORRE / AFP)

The International Brigades

Between 1936 and 1939 at least 35,000 international volunteers from around 50 countries, including around 2,500 Brits, fought against Francisco Franco’s fascist troops in the International Brigade during the Civil War. An estimated 10,000 foreign volunteers died in Spain, according to the Spanish Civil War Museum.

The British novelist George Orwell, who fought with a Communist regiment of the Republican army during the war, described in gory detail the sacrifices of the International Brigades in his seminal work ‘Homage to Catalonia’.

READ ALSO: Remembering the Battle of Jarama and the role of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War

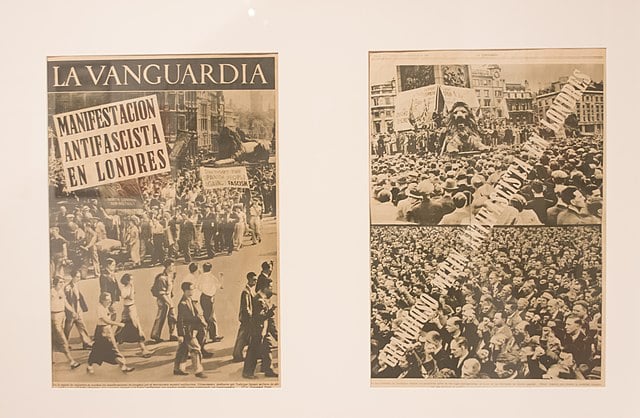

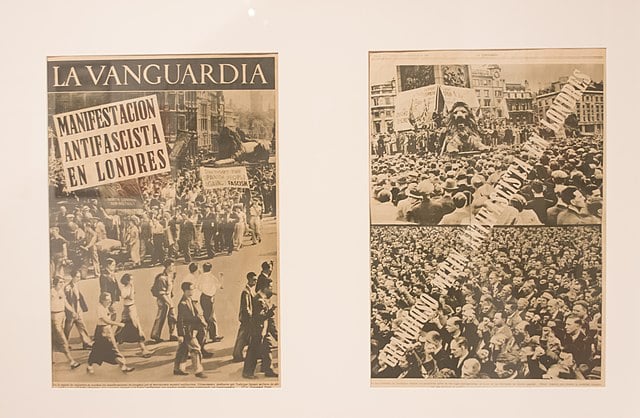

Anti-fascist demonstration in London reported on the front page of Catalan newspaper La Vanguardia on September 11, 1936. Photo: Dorieus/ Wikipedia (CC BY SA 4.0)

What is Spain’s Democratic Memory Law?

The citizenship offer is part of the broader Democratic Memory Law that aims to “settle Spanish democracy’s debt to its past” and deal with the legacy of its Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship.

READ ALSO: Spain’s new ‘grandchildren’ citizenship law: What you need to know

In recent weeks, the Spanish government confirmed that as many as 700,000 foreigners with Spanish lineage are eligible Spanish citizenship without having ever lived in the country, including those with ancestors who fled Spain for fear of persecution during Franco’s dictatorship.

Between the end of the Civil War in 1939, and 1978, when Spain’s new constitution was approved as part of its transition to democracy, an estimated 2 million Spaniards fled the Franco regime.

Controversy

Legislation concerning Spain’s dictatorial past is always controversial, and this law was no different – it passed the Spanish Senate earlier in October with 128 votes in favour, 113 against, and 18 abstentions.

The Spanish right have long been opposed to any kind of historical memory legislation, claiming that it digs up old rivalries and causes political tension. Spain’s centre-right party, the PP, have promised to overturn the law if it wins the next general election.

READ ALSO: Spain’s lawmakers pass bill honouring Franco-era victims

Other aspects of the law include the establishment of a DNA register to help families identify the remains of the tens of thousands of Spaniards were buried in unmarked graves; the repurposing of the Valley of the Fallen mausoleum, where Francisco Franco was buried until his exhumation in 2019; and a ban on groups that glorify the Franco regime.

Comments

See Also

Descendants

The children and grandchildren of fighters who fought for the International Brigades during Spain’s Civil War will be able to acquire Spanish citizenship - and won’t have to give up their other nationality in order to do so.

The fighters themselves have been able to apply for Spanish citizenship since 1996, though they were required to drop their other nationality. Spain’s 2007 Historical Memory Law removed that requirement, though the offer of citizenship was not extended to their descendants.

There was confusion in 2020 when Spain's then deputy Prime Minister Pablo Iglesias tweeted that descendants of International Brigade fighters would be included in legislation, but when the final legal text appeared, it confirmed that the proposal did not stretch to descendants and only included the International Brigade veterans themselves.

Now Spain's new Democratic Memory Law, which passed the Spanish Senate on October 5th and officially became law on October 21st, finally extends the citizenship offer to descendants who can get Spanish nationality without losing theirs.

They will even be able to do it through the fast-tracked naturalisation process - seen as the expressway to Spanish citizenship and used by public figures such as Barcelona footballer Ansu Fati and actress Imperio Argentina.

READ ALSO:

- What are the other ways foreigners can get fast-track Spanish citizenship?

- Do you really have to give up your original nationality to become Spanish?

According to the Asociación de Amigos de las Brigadas Internacionales (AABI), a group involved with drafts of the legislation, there are at least one hundred known descendants that have been identified so far. They come from around the world, including France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Cuba, the former Yugoslavia, Argentina, Canada, Australia, and the United States.

As there are so few descendants of international brigade fighters, however, many view their inclusion in the citizenship legislation as a symbolic gesture that is part of the Democratic Memory Law's efforts to settle historical debts with the past.

Though the legislation does extend citizenship, it's not thought that a flood of applications will follow. "There will be no avalanche, it is a symbolic measure that has a purely sentimental importance for the relatives of the fighters," the AABI explained to Spanish news website Newtral.es.

The International Brigades

Between 1936 and 1939 at least 35,000 international volunteers from around 50 countries, including around 2,500 Brits, fought against Francisco Franco’s fascist troops in the International Brigade during the Civil War. An estimated 10,000 foreign volunteers died in Spain, according to the Spanish Civil War Museum.

The British novelist George Orwell, who fought with a Communist regiment of the Republican army during the war, described in gory detail the sacrifices of the International Brigades in his seminal work ‘Homage to Catalonia’.

READ ALSO: Remembering the Battle of Jarama and the role of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War

What is Spain’s Democratic Memory Law?

The citizenship offer is part of the broader Democratic Memory Law that aims to “settle Spanish democracy’s debt to its past” and deal with the legacy of its Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship.

READ ALSO: Spain’s new ‘grandchildren’ citizenship law: What you need to know

In recent weeks, the Spanish government confirmed that as many as 700,000 foreigners with Spanish lineage are eligible Spanish citizenship without having ever lived in the country, including those with ancestors who fled Spain for fear of persecution during Franco’s dictatorship.

Between the end of the Civil War in 1939, and 1978, when Spain’s new constitution was approved as part of its transition to democracy, an estimated 2 million Spaniards fled the Franco regime.

Controversy

Legislation concerning Spain’s dictatorial past is always controversial, and this law was no different – it passed the Spanish Senate earlier in October with 128 votes in favour, 113 against, and 18 abstentions.

The Spanish right have long been opposed to any kind of historical memory legislation, claiming that it digs up old rivalries and causes political tension. Spain’s centre-right party, the PP, have promised to overturn the law if it wins the next general election.

READ ALSO: Spain’s lawmakers pass bill honouring Franco-era victims

Other aspects of the law include the establishment of a DNA register to help families identify the remains of the tens of thousands of Spaniards were buried in unmarked graves; the repurposing of the Valley of the Fallen mausoleum, where Francisco Franco was buried until his exhumation in 2019; and a ban on groups that glorify the Franco regime.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.