Charming or boring - What do Italians think of life in the old town?

Most towns in Italy have a pretty 'centro storico', or old town centre, full of charm and history. But there are plenty of reasons why Italians don't want to live there, says Silvia Marchetti.

Italy’s rural villages lure foreigners with their fascinating historic centres and bucolic vibe, but they’re not always as idyllic as they may seem at first glance.

Living in such villages, many of which are depopulated and in isolated places, built around a more or less intact ancient district, has pros and cons. They come with caveats.

The plus points are of course the old architecture and picturesque buildings full of history, surroundings with great countryside or mountain views, fewer crowds, authentic food and traditions, and welcoming neighbours. There is that ‘microcosm’ ambiance that makes you feel at home in a small place.

But one must go beyond the romantic, aesthetic appeal of old districts and look at how practical it is to actually live there.

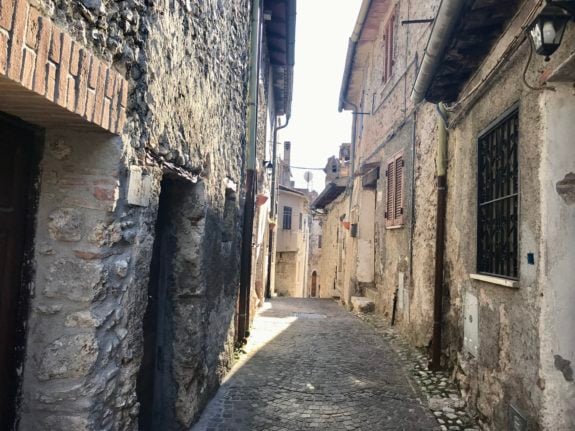

Last weekend I visited a small village in the province of Rieti called Percile and nearly broke my leg climbing up and down the layers of huge stone steps, which were the actual alleys, wondering how residents could do it every single time they left their homes. It’s like a killer open-air gym.

READ ALSO: How to spot Italy’s ‘fake authentic’ tourist villages

While some foreigners might view such daily feats as part of their sogno all’italiana (‘Italian dream’), Italians are not as keen on reliving the bygone days.

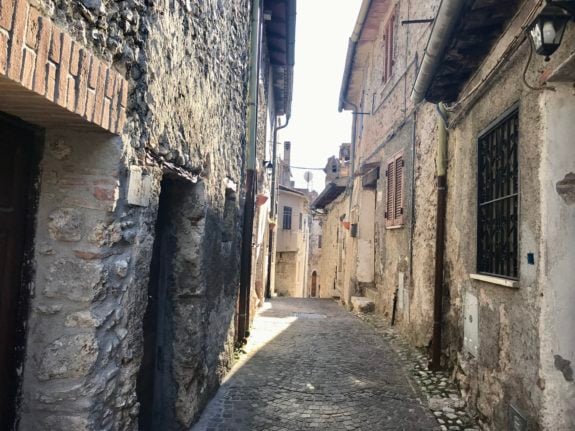

Historic centres are all structured in the same way: a bunch of houses cropped at the feet of a castle, church or fortress, with narrow, winding cobbled alleys where ankles get easily sprained, and ragged stone steps connecting the various levels.

The semi-deserted old town centre of Rignano Flaminio. Photo: Silvia Marchetti

Cars are banned, finding a parking place nearby is hell, especially in summer, and the pavements get slippery when it rains. And in small villages where most locals have long left, or return just for weekends, shops, bars, restaurants and pharmacies tend to be located in newer areas or in nearby towns.

In the past locals fled from these places due to harsh living conditions, searching for a brighter future elsewhere. They left behind empty houses, so today many historic centres are partly abandoned and inhabited by adventurous foreigners looking for a quiet retreat.

Italians tend not to buy houses in old neighbourhoods unless they have nostalgia for their roots and want to reconnect with their ancestors, or eye an investment like a B&B. They’d rather buy country houses with a garden, plot of land, and if affordable, a small pool.

READ ALSO: Why Italians aren't snatching up their country's one-euro homes

My Italian friends have never even considered buying an old dwelling in the historic centre of a rural village; they find it uncomfortable. And so do I, unless I’m sure to have everything I need at hand and at a short walking distance.

“I’m Sicilian, but I’d never purchase a cheap or one-euro home in Sicily’s ancient neighbourhoods, no matter how fascinating these are. I would not know where to park the car and just the thought of carrying heavy grocery bags and bottled water up staircases scares me, old homes don’t come with elevators”, says Rosi Gangiulo, a pensioner from Palermo.

Crumbling houses in Percile. Photo: Silvia Marchetti

There are also a few prejudices involved too. Unless it’s a unique, stunning town like Civita di Bagnoreggio in Lazio suspended above a deep chasm, or Renaissance-era jewel Pienza in Tuscany, living in the old part is seen as (and often is) the place for poorer families, while owning an attic in the newer area where all the pubs and shops are is ‘cool’.

In the medieval historic centre of Rignano Flaminio north of Rome, few locals remain, hens run freely amid grass-covered ruins, and entire families of immigrants live cramped in tiny one-room apartments.

Former Italian residents have moved to the countryside or to the modern outskirts, certainly less charming but easier to live in.

Some seemingly picture-perfect historical centres are best admired at a distance, rather than experienced from the inside. Last time I visited Torrita Tiberina in the Tiber Valley it struck me how most homes in the medieval district were shut, abandoned or decaying, with nobody around.

I happened to bump into a young Neapolitan man who asked me whether I knew what time the bus to Rome was. He told me he had been living there for four months, focusing on writing a book.

“The silence is great but it’s just too quiet. I don’t have a car and each time I had to buy something I needed to get out of the historic centre. It also became unbearable having no next-door neighbour to chat with.

To be sure old villages are the right fit, one has to look beyond the charm and really evaluate whether they’re liveable as well as beautiful.

Comments (1)

See Also

Italy’s rural villages lure foreigners with their fascinating historic centres and bucolic vibe, but they’re not always as idyllic as they may seem at first glance.

Living in such villages, many of which are depopulated and in isolated places, built around a more or less intact ancient district, has pros and cons. They come with caveats.

The plus points are of course the old architecture and picturesque buildings full of history, surroundings with great countryside or mountain views, fewer crowds, authentic food and traditions, and welcoming neighbours. There is that ‘microcosm’ ambiance that makes you feel at home in a small place.

But one must go beyond the romantic, aesthetic appeal of old districts and look at how practical it is to actually live there.

Last weekend I visited a small village in the province of Rieti called Percile and nearly broke my leg climbing up and down the layers of huge stone steps, which were the actual alleys, wondering how residents could do it every single time they left their homes. It’s like a killer open-air gym.

READ ALSO: How to spot Italy’s ‘fake authentic’ tourist villages

While some foreigners might view such daily feats as part of their sogno all’italiana (‘Italian dream’), Italians are not as keen on reliving the bygone days.

Historic centres are all structured in the same way: a bunch of houses cropped at the feet of a castle, church or fortress, with narrow, winding cobbled alleys where ankles get easily sprained, and ragged stone steps connecting the various levels.

Cars are banned, finding a parking place nearby is hell, especially in summer, and the pavements get slippery when it rains. And in small villages where most locals have long left, or return just for weekends, shops, bars, restaurants and pharmacies tend to be located in newer areas or in nearby towns.

In the past locals fled from these places due to harsh living conditions, searching for a brighter future elsewhere. They left behind empty houses, so today many historic centres are partly abandoned and inhabited by adventurous foreigners looking for a quiet retreat.

Italians tend not to buy houses in old neighbourhoods unless they have nostalgia for their roots and want to reconnect with their ancestors, or eye an investment like a B&B. They’d rather buy country houses with a garden, plot of land, and if affordable, a small pool.

READ ALSO: Why Italians aren't snatching up their country's one-euro homes

My Italian friends have never even considered buying an old dwelling in the historic centre of a rural village; they find it uncomfortable. And so do I, unless I’m sure to have everything I need at hand and at a short walking distance.

“I’m Sicilian, but I’d never purchase a cheap or one-euro home in Sicily’s ancient neighbourhoods, no matter how fascinating these are. I would not know where to park the car and just the thought of carrying heavy grocery bags and bottled water up staircases scares me, old homes don’t come with elevators”, says Rosi Gangiulo, a pensioner from Palermo.

There are also a few prejudices involved too. Unless it’s a unique, stunning town like Civita di Bagnoreggio in Lazio suspended above a deep chasm, or Renaissance-era jewel Pienza in Tuscany, living in the old part is seen as (and often is) the place for poorer families, while owning an attic in the newer area where all the pubs and shops are is ‘cool’.

In the medieval historic centre of Rignano Flaminio north of Rome, few locals remain, hens run freely amid grass-covered ruins, and entire families of immigrants live cramped in tiny one-room apartments.

Former Italian residents have moved to the countryside or to the modern outskirts, certainly less charming but easier to live in.

Some seemingly picture-perfect historical centres are best admired at a distance, rather than experienced from the inside. Last time I visited Torrita Tiberina in the Tiber Valley it struck me how most homes in the medieval district were shut, abandoned or decaying, with nobody around.

I happened to bump into a young Neapolitan man who asked me whether I knew what time the bus to Rome was. He told me he had been living there for four months, focusing on writing a book.

“The silence is great but it’s just too quiet. I don’t have a car and each time I had to buy something I needed to get out of the historic centre. It also became unbearable having no next-door neighbour to chat with.

To be sure old villages are the right fit, one has to look beyond the charm and really evaluate whether they’re liveable as well as beautiful.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.