Why Sweden’s Nobel prizewinner would be a great dinner guest

It is not only Svante Pääbo’s contribution to evolutionary biology that makes him so interesting, but his own personal story as well, says David Crouch.

Elite scientists are maybe not so high on our list of fantasy dinner guests. Too much homework before the conversation. But the more I find out about Svante Pääbo, the Swedish winner of this year’s Nobel prize for medicine, the more I am convinced he would be great company.

A modest man with a delightful smile, who likes beer and schnapps with lunch and listens to rock band Talking Heads, Pääbo comes across as warm and approachable. When he won the Nobel, his colleagues at the university threw him in a pond. His book Neanderthal Man is peppered with praise for students and colleagues who helped him along the way.

He is also skilled at explaining in simple and engaging terms what his research means for all of us. At a time when immigration is such a hot potato, Pääbo reminds us that the history of our species is one of movement and mingling of populations.

It is not only Pääbo’s contribution to evolutionary biology that makes this clear, but his own personal story as well.

Aged 19, his mother Karin fled her native Estonia in 1944, joining tens of thousands who escaped the Soviet occupation. She worked as a cleaner and a cook in Kalmar, then studied chemistry in Lund, where she met Svante’s father.

But he was married. Karin brought up her son alone in Stockholm. The father visited on Saturdays when his family thought he was at work.

Svante followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a researcher. A surreptitious experiment in the lab with a piece of liver from ICA set him on a path towards discovering how to extract and study DNA from long-dead animals. At Uppsala University he was also a gay rights activist, before he fell in love with the “boyish charms” of a female colleague at Berkeley, with whom he went on to share his life and have two children.

Pääbo says it came as a surprise that his bisexuality was considered unusual, and the fact that it didn’t cause him any problems he contributes to the high self-esteem that his mother had given him. “The realisation that my feelings were not quite what the majority society expected forced me to change my rather complacent attitude and led over time to me becoming more open,” he said in a talk on Swedish radio. “Not only to myself, but also for the idiosyncrasies of others.”

Pääbo developed the ideas and techniques that enabled the DNA of our closest genetic relative, the Neanderthals, to be fully decoded and compared to human DNA. His work shows that, as early humans moved east and north from Africa some 70,000 years ago, they mingled and mated with Neanderthals, their mixed children living in human communities and passing on their genes.

“From a genomic perspective, we are all Africans – either living in Africa or in quite recent exile,” Pääbo says. But many of us have Neanderthal DNA, around 2.5% of the total – we are more Neanderthal the further you get from Africa, in fact. “The lesson is that we have always mixed. We mixed with these earlier forms of humans, wherever we met them, and we mixed with each other ever since,” Pääbo says.

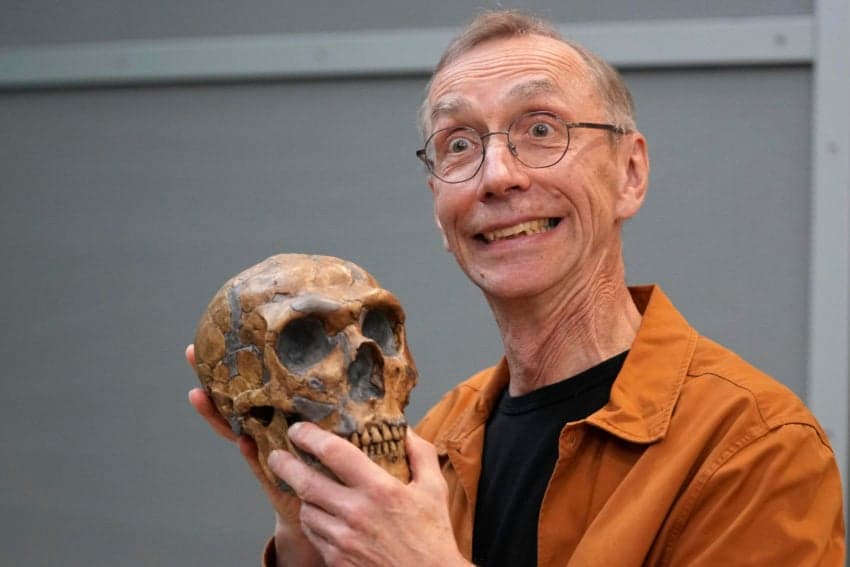

Swedish scientist Svante Paabo swims in a pool at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Photo: Matthias Schrader/AP/AFP

Pääbo’s research has relevance for modern medicine because he has enabled scientists to examine how viruses have changed with time. Last year, he and his team made headlines when they reported that people with a Neanderthal variant of their third chromosome were at a higher risk of suffering severe consequences from contracting Covid-19.

As a dinner guest, I think Pääbo would bring the outlook of a person who has experienced both east and west. The Stasi, the east German secret police, investigated after he was given tissue samples from Egyptian mummies at a museum in East Berlin. He moved from California to live and work in Munich, and then the former east-German city of Leipzig. Some of his seminal work is on samples found by Russian researchers in a cave in Denisova, a remote spot in Siberian mountains near the borders with Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia.

It is wise to avoid politics at dinner parties, but Pääbo might also have something interesting to say about Sweden today.

Julia Kronlid, newly-elected to the post of vice speaker of parliament, is a senior member of the Sweden Democrats and someone who does not accept the theory of evolution. In 2014, she said in a widely cited interview: “I do not accept the theory of evolution’s claim that humans are descended from apes. One can question the scientific nature of it because it is so far back in time.”

By all accounts, Kronlid appears to be a nice person, whatever you think of her politics or beliefs. Hopefully, she celebrates the Nobel prize for medicine as a great Swedish achievement. And wouldn’t it be nice if she and Pääbo could sit down to dinner together sometime soon?

David Crouch is the author of Almost Perfekt: How Sweden Works and What Can We Learn From It. He is a freelance journalist and a lecturer in journalism at Gothenburg University.

Comments

See Also

Elite scientists are maybe not so high on our list of fantasy dinner guests. Too much homework before the conversation. But the more I find out about Svante Pääbo, the Swedish winner of this year’s Nobel prize for medicine, the more I am convinced he would be great company.

A modest man with a delightful smile, who likes beer and schnapps with lunch and listens to rock band Talking Heads, Pääbo comes across as warm and approachable. When he won the Nobel, his colleagues at the university threw him in a pond. His book Neanderthal Man is peppered with praise for students and colleagues who helped him along the way.

He is also skilled at explaining in simple and engaging terms what his research means for all of us. At a time when immigration is such a hot potato, Pääbo reminds us that the history of our species is one of movement and mingling of populations.

It is not only Pääbo’s contribution to evolutionary biology that makes this clear, but his own personal story as well.

Aged 19, his mother Karin fled her native Estonia in 1944, joining tens of thousands who escaped the Soviet occupation. She worked as a cleaner and a cook in Kalmar, then studied chemistry in Lund, where she met Svante’s father.

But he was married. Karin brought up her son alone in Stockholm. The father visited on Saturdays when his family thought he was at work.

Svante followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a researcher. A surreptitious experiment in the lab with a piece of liver from ICA set him on a path towards discovering how to extract and study DNA from long-dead animals. At Uppsala University he was also a gay rights activist, before he fell in love with the “boyish charms” of a female colleague at Berkeley, with whom he went on to share his life and have two children.

Pääbo says it came as a surprise that his bisexuality was considered unusual, and the fact that it didn’t cause him any problems he contributes to the high self-esteem that his mother had given him. “The realisation that my feelings were not quite what the majority society expected forced me to change my rather complacent attitude and led over time to me becoming more open,” he said in a talk on Swedish radio. “Not only to myself, but also for the idiosyncrasies of others.”

Pääbo developed the ideas and techniques that enabled the DNA of our closest genetic relative, the Neanderthals, to be fully decoded and compared to human DNA. His work shows that, as early humans moved east and north from Africa some 70,000 years ago, they mingled and mated with Neanderthals, their mixed children living in human communities and passing on their genes.

“From a genomic perspective, we are all Africans – either living in Africa or in quite recent exile,” Pääbo says. But many of us have Neanderthal DNA, around 2.5% of the total – we are more Neanderthal the further you get from Africa, in fact. “The lesson is that we have always mixed. We mixed with these earlier forms of humans, wherever we met them, and we mixed with each other ever since,” Pääbo says.

Pääbo’s research has relevance for modern medicine because he has enabled scientists to examine how viruses have changed with time. Last year, he and his team made headlines when they reported that people with a Neanderthal variant of their third chromosome were at a higher risk of suffering severe consequences from contracting Covid-19.

As a dinner guest, I think Pääbo would bring the outlook of a person who has experienced both east and west. The Stasi, the east German secret police, investigated after he was given tissue samples from Egyptian mummies at a museum in East Berlin. He moved from California to live and work in Munich, and then the former east-German city of Leipzig. Some of his seminal work is on samples found by Russian researchers in a cave in Denisova, a remote spot in Siberian mountains near the borders with Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia.

It is wise to avoid politics at dinner parties, but Pääbo might also have something interesting to say about Sweden today.

Julia Kronlid, newly-elected to the post of vice speaker of parliament, is a senior member of the Sweden Democrats and someone who does not accept the theory of evolution. In 2014, she said in a widely cited interview: “I do not accept the theory of evolution’s claim that humans are descended from apes. One can question the scientific nature of it because it is so far back in time.”

By all accounts, Kronlid appears to be a nice person, whatever you think of her politics or beliefs. Hopefully, she celebrates the Nobel prize for medicine as a great Swedish achievement. And wouldn’t it be nice if she and Pääbo could sit down to dinner together sometime soon?

David Crouch is the author of Almost Perfekt: How Sweden Works and What Can We Learn From It. He is a freelance journalist and a lecturer in journalism at Gothenburg University.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.