How Europe's population is changing and what the EU is doing about it

The populations of countries across Europe are changing, with some increasing whilst others are falling. Populations are also ageing meaning the EU is having to react to changing demographics.

After decades of growth, the population of the European Union decreased over the past two years mostly due to the hundreds of thousands of deaths caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The latest data from the EU statistical office Eurostat show that the EU population was 446.8 million on 1 January 2022, 172,000 fewer than the previous year. On 1 January 2020, the EU had a population of 447.3 million.

This trend is because, in 2020 and 2021 the two years marked by the crippling pandemic, there have been more deaths than births and the negative natural change has been more significant than the positive net migration.

But there are major differences across countries. For example, in numerical terms, Italy is the country where the population has decreased the most, while France has recorded the largest increase.

What is happening and how is the EU reacting?

In which countries is the population growing?

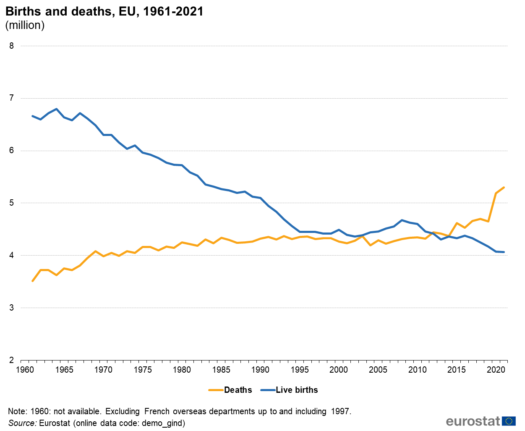

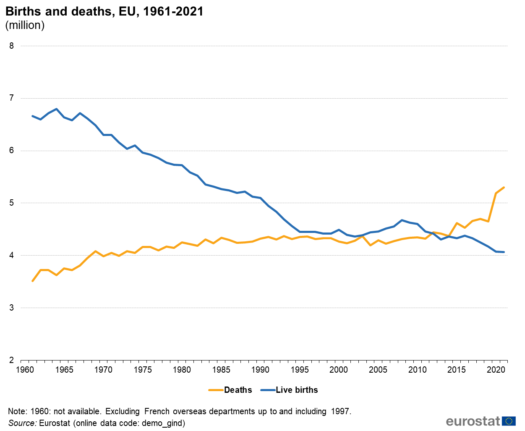

In 2021, there were almost 4.1 million births and 5.3 million deaths in the EU, so the natural change was negative by 1.2 million (more broadly, there were 113,000 more deaths in 2021 than in 2020 and 531,000 more deaths in 2020 than in 2019, while the number of births remained almost the same).

Net migration, the number of people arriving in the EU minus those leaving, was 1.1 million, not enough to compensate.

A population growth, however, was recorded in 17 countries. Nine (Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, France, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands and Sweden) had both a natural increase and positive net migration.

READ ALSO: IN NUMBERS: Five things to know about Germany’s foreign population

In eight EU countries (the Czech Republic, Germany, Estonia, Spain, Lithuania, Austria, Portugal and Finland), the population increased because of positive net migration, while the natural change was negative.

The largest increase in absolute terms was in France (+185,900). The highest natural increase was in Ireland (5.0 per 1,000 persons), while the biggest growth rate relative to the existing population was recorded in Luxembourg, Ireland, Cyprus and Malta (all above 8.0 per 1,000 persons).

In total, 22 EU Member States had positive net migration, with Luxembourg (13.2 per 1 000 persons), Lithuania (12.4) and Portugal (9.6) topping the list.

Births and deaths in the EU from 1961 to 2021 (Eurostat)

Where is the population declining?

On the other hand, 18 EU countries had negative rates of natural change, with deaths outnumbering births in 2021.

Ten of these recorded a population decline. In Bulgaria, Italy, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia population declined due to a negative natural change, while net migration was slightly positive.

In Croatia, Greece, Latvia, Romania and Slovakia, the decrease was both by negative natural change and negative net migration.

READ ALSO: Italian class sizes set to shrink as population falls further

The largest fall in population was reported in Italy, which lost over a quarter of a million (-253,100).

The most significant negative natural change was in Bulgaria (-13.1 per 1,000 persons), Latvia (-9.1), Lithuania (-8.7) and Romania (-8.2). On a proportional basis, Croatia and Bulgaria recorded the biggest population decline (-33.1 per 1,000 persons).

How is the EU responding to demographic change?

From 354.5 million in 1960, the EU population grew to 446.8 million on 1 January 2022, an increase of 92.3 million. If the growth was about 3 million persons per year in the 1960s, it slowed to about 0.7 million per year on average between 2005 and 2022, according to Eurostat.

The natural change was positive until 2011 and turned negative in 2012 when net migration became the key factor for population growth. However, in 2020 and 2021, this no longer compensated for natural change and led to a decline.

READ ALSO: IN NUMBERS: One in four Austrian residents now of foreign origin

Over time, says Eurostat, the negative natural change is expected to continue given the ageing of the population if the fertility rate (total number of children born to each woman) remains low.

This poses questions for the future of the labour market and social security services, such as pensions and healthcare.

The European Commission estimates that by 2070, 30.3 per cent of the EU population will be 65 or over compared to 20.3 per cent in 2019, and 13.2 per cent is projected to be 80 or older compared to 5.8 per cent in 2019.

The number of people needing long-term care is expected to increase from 19.5 million in 2016 to 23.6 million in 2030 and 30.5 million in 2050.

READ ALSO: How foreigners are changing Switzerland

However, demographic change impacts different countries and often regions within the same country differently.

When she took on the Presidency of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen appointed Dubravka Šuica, a Croatian politician, as Commissioner for Democracy and Demography to deal with these changes.

Among measures in the discussion, in January 2021, the Commission launched a debate on Europe's ageing society, suggesting steps for higher labour market participation, including more equality between women and men and longer working lives.

In April, the Commission proposed measures to make Europe more attractive for foreign workers, including simplifying rules for non-EU nationals who live on a long-term basis in the EU. These will have to be approved by the European Parliament and the EU Council.

In the fourth quarter of this year, the Commission also plans to present a communication on dealing with ‘brain drain’ and mitigate the challenges associated with population decline in regions with low birth rates and high net emigration.

This article is published in cooperation with Europe Street News, a news outlet about citizens’ rights in the EU and the UK.

Comments

See Also

After decades of growth, the population of the European Union decreased over the past two years mostly due to the hundreds of thousands of deaths caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The latest data from the EU statistical office Eurostat show that the EU population was 446.8 million on 1 January 2022, 172,000 fewer than the previous year. On 1 January 2020, the EU had a population of 447.3 million.

This trend is because, in 2020 and 2021 the two years marked by the crippling pandemic, there have been more deaths than births and the negative natural change has been more significant than the positive net migration.

But there are major differences across countries. For example, in numerical terms, Italy is the country where the population has decreased the most, while France has recorded the largest increase.

What is happening and how is the EU reacting?

In which countries is the population growing?

In 2021, there were almost 4.1 million births and 5.3 million deaths in the EU, so the natural change was negative by 1.2 million (more broadly, there were 113,000 more deaths in 2021 than in 2020 and 531,000 more deaths in 2020 than in 2019, while the number of births remained almost the same).

Net migration, the number of people arriving in the EU minus those leaving, was 1.1 million, not enough to compensate.

A population growth, however, was recorded in 17 countries. Nine (Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, France, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands and Sweden) had both a natural increase and positive net migration.

READ ALSO: IN NUMBERS: Five things to know about Germany’s foreign population

In eight EU countries (the Czech Republic, Germany, Estonia, Spain, Lithuania, Austria, Portugal and Finland), the population increased because of positive net migration, while the natural change was negative.

The largest increase in absolute terms was in France (+185,900). The highest natural increase was in Ireland (5.0 per 1,000 persons), while the biggest growth rate relative to the existing population was recorded in Luxembourg, Ireland, Cyprus and Malta (all above 8.0 per 1,000 persons).

In total, 22 EU Member States had positive net migration, with Luxembourg (13.2 per 1 000 persons), Lithuania (12.4) and Portugal (9.6) topping the list.

Where is the population declining?

On the other hand, 18 EU countries had negative rates of natural change, with deaths outnumbering births in 2021.

Ten of these recorded a population decline. In Bulgaria, Italy, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia population declined due to a negative natural change, while net migration was slightly positive.

In Croatia, Greece, Latvia, Romania and Slovakia, the decrease was both by negative natural change and negative net migration.

READ ALSO: Italian class sizes set to shrink as population falls further

The largest fall in population was reported in Italy, which lost over a quarter of a million (-253,100).

The most significant negative natural change was in Bulgaria (-13.1 per 1,000 persons), Latvia (-9.1), Lithuania (-8.7) and Romania (-8.2). On a proportional basis, Croatia and Bulgaria recorded the biggest population decline (-33.1 per 1,000 persons).

How is the EU responding to demographic change?

From 354.5 million in 1960, the EU population grew to 446.8 million on 1 January 2022, an increase of 92.3 million. If the growth was about 3 million persons per year in the 1960s, it slowed to about 0.7 million per year on average between 2005 and 2022, according to Eurostat.

The natural change was positive until 2011 and turned negative in 2012 when net migration became the key factor for population growth. However, in 2020 and 2021, this no longer compensated for natural change and led to a decline.

READ ALSO: IN NUMBERS: One in four Austrian residents now of foreign origin

Over time, says Eurostat, the negative natural change is expected to continue given the ageing of the population if the fertility rate (total number of children born to each woman) remains low.

This poses questions for the future of the labour market and social security services, such as pensions and healthcare.

The European Commission estimates that by 2070, 30.3 per cent of the EU population will be 65 or over compared to 20.3 per cent in 2019, and 13.2 per cent is projected to be 80 or older compared to 5.8 per cent in 2019.

The number of people needing long-term care is expected to increase from 19.5 million in 2016 to 23.6 million in 2030 and 30.5 million in 2050.

READ ALSO: How foreigners are changing Switzerland

However, demographic change impacts different countries and often regions within the same country differently.

When she took on the Presidency of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen appointed Dubravka Šuica, a Croatian politician, as Commissioner for Democracy and Demography to deal with these changes.

Among measures in the discussion, in January 2021, the Commission launched a debate on Europe's ageing society, suggesting steps for higher labour market participation, including more equality between women and men and longer working lives.

In April, the Commission proposed measures to make Europe more attractive for foreign workers, including simplifying rules for non-EU nationals who live on a long-term basis in the EU. These will have to be approved by the European Parliament and the EU Council.

In the fourth quarter of this year, the Commission also plans to present a communication on dealing with ‘brain drain’ and mitigate the challenges associated with population decline in regions with low birth rates and high net emigration.

This article is published in cooperation with Europe Street News, a news outlet about citizens’ rights in the EU and the UK.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.