How did Sweden tackle the Spanish flu a century ago?

Almost exactly a hundred years ago another pandemic raged across the world. The disease, known as the Spanish flu, had an extremely high – and unusual – death toll, mostly affecting young, healthy people. What did the Swedish government at the time do to curb the spread of the virus? How successful was their strategy? And: are there any take-aways for today's coronavirus crisis?

Where exactly it originated remains unknown. Patient zero will never be recovered from history. But what is known is that sometime in the spring of 1918, during the final phases of the Great War that would later enter public memory as the First World War, an unusual type of infection started spreading.

It had seemed common enough at first, sharing most of its features with the seasonal flu, which in part explains why it proved impossible to point to its origins. It had first been detected in North America, but who knows where it had travelled before, well disguised as a fierce winter cold?

So the Spanish flu, which was the name the strange, lethal disease came to be known by, was not, in fact, Spanish? Well, no. The virus – which only later became known as a virus, having arrived in an era in which microscopes couldn't detect anything as small as a virus yet – merely became widely known in Spain, from where news spread speedily about King Alfonso XIII's illness and the catastrophic infection rate in San Sebastian.

The infection wasn't uniquely Spanish. However, what was unique was that Spain, a neutral nation during the First World War, was one of the few countries that hadn't imposed strict censorship. So even though the disease was already raging in a number of countries, most of the tragic stories came from the Iberian peninsula.

From March 1918 onwards the new disease spread rapidly, partly but not only due to troops moving across borders. Even in a world before chartered airplanes and affordable overseas travelling, the virus managed to cross oceans, reach all continents and affect the most isolated communities, from the Arctic to the Samoa Islands.

"It's a common misconception that today's situation is new in its scope because of globalisation," historian and journalist Magnus Västerbro told The Local. "We've been living in a globalised world for centuries. A hundred years ago we already had fast connections."

They may not have been as fast as today, but they were fast enough; fast enough to reach pretty much every corner of the globe within the time frame the virus was around, between 1918 and 1920. There were steamboats, trains, cars. The virus, Västerbro said, first arrived at large traffic hubs, like harbours, and from there moved along roads and railroads further inland.

The virus followed the same trajectory in Sweden, the first diagnoses being made in Stockholm and Skåne, in the south, but steadily moving northwards reaching the last bastions, far up north in Lapland, in 1920.

This fact, Västerbro concluded, captures a lesson for today's coronavirus crisis.

"It's practically impossible to stop the spread and to completely isolate regions or countries. Especially in the long run, you're unlikely to succeed in keeping the virus at bay," he said.

"Look at New Zealand, for example, a country that thus far has been able to by and large steer clear of the pandemic. But they would have to remain in a state of lockdown for a really long time, would they stand a chance to keep the disease out indefinitely. A vaccine won't be available in the near future, and it only takes the arrival of one infected traveller."

In Sweden, too, the pandemic arrived as a seemingly common enough influenza. It was only in July 1918, when a large outbreak occurred, that it started to stand out; it was the midst of summer, a highly unusual period for the flu. Swedes started getting infected in huge numbers, at first experiencing mostly mild symptoms, but the virus soon enough started killing young men and women left and right.

"This was the reason the disease was so terrifying. A cynic could argue that the old and vulnerable who usually fall victim to epidemics, well, would probably have died soon anyway. But a virus that took a generation of young adults? That was unheard of. It interferes with the order of things," Västerbro told The Local.

One theory for this is that the immune system of the young started to overreact, thereby attacking, as it were, their own body. Another factor was that many people got infected with a bacterial pneumonia, which often proved lethal in this pre-antibiotics era.

And even though the virus – any virus – couldn't be made out with a microscope in the early 20th century, doctors at the time did agree that the disease had to be some kind of bacterial infection, prompting state authorities to take measures accordingly. Or, with modern-day semantics: halt the spread of the virus by promoting or demanding social distancing.

With the onset of the autumn of 1918 the virus had spread widely within Sweden. Still, the responsible authorities chose to lay low, even though several influential voices demanded the temporary closure of schools, restaurants and cinemas. Those in power, however, thought these measures unnecessary or excessive.

It was up to the regions to make these calls, but far-reaching measures were rarely taken. In Västerås, for example, the local authorities decided to close the city's cinemas. This ban was lifted shortly thereafter as cinema owners protested the forced closures.

The Swedish government was engrossed in other matters – more important matters, or so it reasoned. The Great War was still raging in Europe and the Swedish state, though neutral, was afraid to be drawn in.

And so it was decided that Sweden would go through with a large-scale military exercise. Mere months before the end of the war all 117,000 conscripts were summoned to participate, despite the fact that abroad, in war-torn Europe, the Spanish flu proved to be especially lethal among young soldiers in overcrowded barracks.

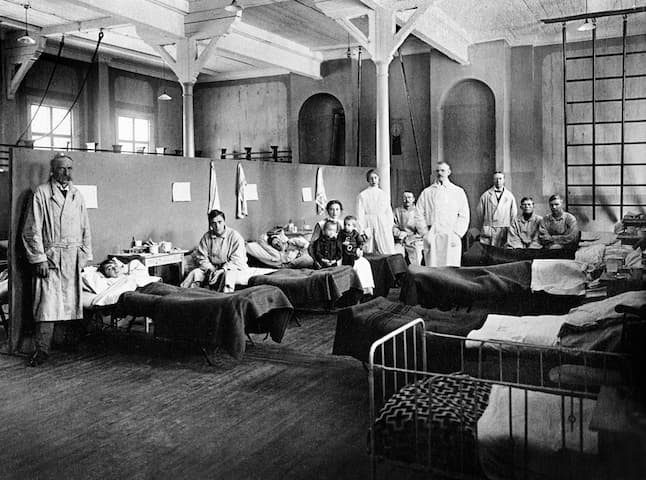

The exercises resulted in a tragedy. Military hospitals around the country overflowed with infected conscripts. Around one third of all soldiers contracted the Spanish flu.

Over the span of two years the virus killed around 40,000 confirmed victims in Sweden, the actual death toll assumed to far exceed that number.

All in all, the government's reaction hadn't been very forceful, Västerbro said: "They lacked resources, and, moreover, they were afraid of the economic consequences of shutting down the country. They made some cardinal mistakes during the course of the pandemic, and realised it soon after."

There was no strategy, no long-term plan, the historian argues. "The main thought was: you can't stop the infection, so the only thing we can do is mobilise all possible medical staff – doctors, nurses, assistant nurses who had been trained in case the nation would become involved in the war, even medical students."

It wasn't enough. There was little organisation, the hospitals didn't have sufficient capacity and medical personnel, often fitting the criteria 'young and healthy', contracted the Spanish flu while taking care of patients.

Does Västerbro then draw parallels to Sweden's approach to the coronavirus crisis, which, according to critics, is overly lax?

"The government's measures today are much harder than a century ago, though still fairly mild compared to other countries," he said. "And I think the Swedish approach is quite reasonable, taking into account that this disease actually isn't that dangerous. It's nothing like the plague, small-pox, or the Spanish flu."

Comments (2)

See Also

Where exactly it originated remains unknown. Patient zero will never be recovered from history. But what is known is that sometime in the spring of 1918, during the final phases of the Great War that would later enter public memory as the First World War, an unusual type of infection started spreading.

It had seemed common enough at first, sharing most of its features with the seasonal flu, which in part explains why it proved impossible to point to its origins. It had first been detected in North America, but who knows where it had travelled before, well disguised as a fierce winter cold?

So the Spanish flu, which was the name the strange, lethal disease came to be known by, was not, in fact, Spanish? Well, no. The virus – which only later became known as a virus, having arrived in an era in which microscopes couldn't detect anything as small as a virus yet – merely became widely known in Spain, from where news spread speedily about King Alfonso XIII's illness and the catastrophic infection rate in San Sebastian.

The infection wasn't uniquely Spanish. However, what was unique was that Spain, a neutral nation during the First World War, was one of the few countries that hadn't imposed strict censorship. So even though the disease was already raging in a number of countries, most of the tragic stories came from the Iberian peninsula.

From March 1918 onwards the new disease spread rapidly, partly but not only due to troops moving across borders. Even in a world before chartered airplanes and affordable overseas travelling, the virus managed to cross oceans, reach all continents and affect the most isolated communities, from the Arctic to the Samoa Islands.

"It's a common misconception that today's situation is new in its scope because of globalisation," historian and journalist Magnus Västerbro told The Local. "We've been living in a globalised world for centuries. A hundred years ago we already had fast connections."

They may not have been as fast as today, but they were fast enough; fast enough to reach pretty much every corner of the globe within the time frame the virus was around, between 1918 and 1920. There were steamboats, trains, cars. The virus, Västerbro said, first arrived at large traffic hubs, like harbours, and from there moved along roads and railroads further inland.

The virus followed the same trajectory in Sweden, the first diagnoses being made in Stockholm and Skåne, in the south, but steadily moving northwards reaching the last bastions, far up north in Lapland, in 1920.

This fact, Västerbro concluded, captures a lesson for today's coronavirus crisis.

"It's practically impossible to stop the spread and to completely isolate regions or countries. Especially in the long run, you're unlikely to succeed in keeping the virus at bay," he said.

"Look at New Zealand, for example, a country that thus far has been able to by and large steer clear of the pandemic. But they would have to remain in a state of lockdown for a really long time, would they stand a chance to keep the disease out indefinitely. A vaccine won't be available in the near future, and it only takes the arrival of one infected traveller."

In Sweden, too, the pandemic arrived as a seemingly common enough influenza. It was only in July 1918, when a large outbreak occurred, that it started to stand out; it was the midst of summer, a highly unusual period for the flu. Swedes started getting infected in huge numbers, at first experiencing mostly mild symptoms, but the virus soon enough started killing young men and women left and right.

"This was the reason the disease was so terrifying. A cynic could argue that the old and vulnerable who usually fall victim to epidemics, well, would probably have died soon anyway. But a virus that took a generation of young adults? That was unheard of. It interferes with the order of things," Västerbro told The Local.

One theory for this is that the immune system of the young started to overreact, thereby attacking, as it were, their own body. Another factor was that many people got infected with a bacterial pneumonia, which often proved lethal in this pre-antibiotics era.

And even though the virus – any virus – couldn't be made out with a microscope in the early 20th century, doctors at the time did agree that the disease had to be some kind of bacterial infection, prompting state authorities to take measures accordingly. Or, with modern-day semantics: halt the spread of the virus by promoting or demanding social distancing.

With the onset of the autumn of 1918 the virus had spread widely within Sweden. Still, the responsible authorities chose to lay low, even though several influential voices demanded the temporary closure of schools, restaurants and cinemas. Those in power, however, thought these measures unnecessary or excessive.

It was up to the regions to make these calls, but far-reaching measures were rarely taken. In Västerås, for example, the local authorities decided to close the city's cinemas. This ban was lifted shortly thereafter as cinema owners protested the forced closures.

The Swedish government was engrossed in other matters – more important matters, or so it reasoned. The Great War was still raging in Europe and the Swedish state, though neutral, was afraid to be drawn in.

And so it was decided that Sweden would go through with a large-scale military exercise. Mere months before the end of the war all 117,000 conscripts were summoned to participate, despite the fact that abroad, in war-torn Europe, the Spanish flu proved to be especially lethal among young soldiers in overcrowded barracks.

The exercises resulted in a tragedy. Military hospitals around the country overflowed with infected conscripts. Around one third of all soldiers contracted the Spanish flu.

Over the span of two years the virus killed around 40,000 confirmed victims in Sweden, the actual death toll assumed to far exceed that number.

All in all, the government's reaction hadn't been very forceful, Västerbro said: "They lacked resources, and, moreover, they were afraid of the economic consequences of shutting down the country. They made some cardinal mistakes during the course of the pandemic, and realised it soon after."

There was no strategy, no long-term plan, the historian argues. "The main thought was: you can't stop the infection, so the only thing we can do is mobilise all possible medical staff – doctors, nurses, assistant nurses who had been trained in case the nation would become involved in the war, even medical students."

It wasn't enough. There was little organisation, the hospitals didn't have sufficient capacity and medical personnel, often fitting the criteria 'young and healthy', contracted the Spanish flu while taking care of patients.

Does Västerbro then draw parallels to Sweden's approach to the coronavirus crisis, which, according to critics, is overly lax?

"The government's measures today are much harder than a century ago, though still fairly mild compared to other countries," he said. "And I think the Swedish approach is quite reasonable, taking into account that this disease actually isn't that dangerous. It's nothing like the plague, small-pox, or the Spanish flu."

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.