Stockholm drone entrepreneur faces deportation for cutting own salary

A Stockholm-based drone entrepreneur has been ordered to leave Sweden within a month after the Migration Agency confirmed its decision to deny him a work visa extension because he went several months without a salary.

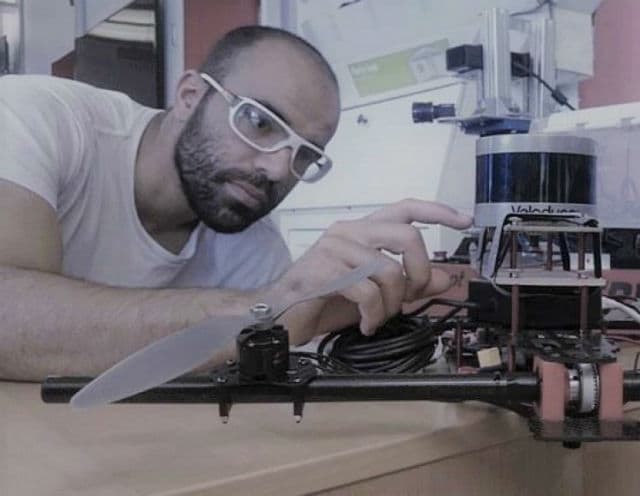

Ahmed Alnomany arrived in Sweden in 2015 and has since set up a mining drone company Inkonova, based at the THINGS startup hub at KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Last month Inkonova raised 3.1 million kronor from Japan's Terra Drone in return for "a significant stake". This came just months after Swedish mining giant LKAB and the world's largest gold miner Barrick Gold both contracted it to scan mines using the Batonomous system, the first commercial scanning jobs for its drones.

But on Friday, Alnomany was ordered to leave the country, a decision he hopes to appeal. He finally got the verdict on an earlier appeal he made in 2017 against a decision to deny him an extension to his work visa.

"After more than a year of waiting, running the business while being locked in the country because I cannot travel, the decision is: yet another refusal from Migrationsverket for my work permit," he told The Local. "This time they added more reasons additional to taking too little salary, including that I took too little vacation."

Alnomany, who was born and grew up in Dubai, said that Sweden needs a better work permit system for foreign entrepreneurs which would allow them to forgo salaries and vacation in the early stages of their companies' development, just as Swedish entrepreneurs invariably do.

"This blindness from the Swedish Migration Agency to this whole process of entrepreneurship is just unjust," he said.

Sweden's government this year stopped working on a long-awaited new law to prevent talented international workers being denied permits for minor administrative errors.

It justified this decision by arguing that a December ruling from the Swedish Migration Court of Appeal now required the Migration Agency to look at the entirety of an individual's case when making decisions, meaning small administrative errors should not result in deportations.

But, as Alnomany's case and many others make clear, skilled workers and entrepreneurs are still being forced to leave Sweden.

"It depends on what you classify as a small mistake," Alnomany said of the agency's new legal framework. "Maybe not taking a salary is not a small mistake."

The entrepreneur said he would now try to appeal the ruling once again, but described his chances of success as "really slim".

"It's not Migrationsverket's fault. They're just applying the rules blindly, so we just need to put some momentum so people can say maybe these rules need to be changed," he said.

"However, I believe that this is an injustice, so I need to fight it to the end and see where it goes."

He said it was particularly frustrating that the ruling had come at a time when the company he co-founded along with was looking increasingly close to becoming profitable.

"Right now we are making progress. Right now we are in a partnership with a Japanese company and starting to sell all over the world," he said. "It took a lot of effort to secure that partnership, and bear in mind that I was locked in the country. I can't go and meet them there. I had to bring their team, their president, here."

With both Alnomany and his co-founder Pau Mallol now well established in Sweden and the company growing fast, he said he still hoped to stay in the country somehow.

"There's not many companies in the world who are doing such things. It's deep tech. I really want to keep it in Swedish borders so that the wider community can benefit," he said.

Comments

See Also

Ahmed Alnomany arrived in Sweden in 2015 and has since set up a mining drone company Inkonova, based at the THINGS startup hub at KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Last month Inkonova raised 3.1 million kronor from Japan's Terra Drone in return for "a significant stake". This came just months after Swedish mining giant LKAB and the world's largest gold miner Barrick Gold both contracted it to scan mines using the Batonomous system, the first commercial scanning jobs for its drones.

But on Friday, Alnomany was ordered to leave the country, a decision he hopes to appeal. He finally got the verdict on an earlier appeal he made in 2017 against a decision to deny him an extension to his work visa.

"After more than a year of waiting, running the business while being locked in the country because I cannot travel, the decision is: yet another refusal from Migrationsverket for my work permit," he told The Local. "This time they added more reasons additional to taking too little salary, including that I took too little vacation."

Alnomany, who was born and grew up in Dubai, said that Sweden needs a better work permit system for foreign entrepreneurs which would allow them to forgo salaries and vacation in the early stages of their companies' development, just as Swedish entrepreneurs invariably do.

"This blindness from the Swedish Migration Agency to this whole process of entrepreneurship is just unjust," he said.

Sweden's government this year stopped working on a long-awaited new law to prevent talented international workers being denied permits for minor administrative errors.

It justified this decision by arguing that a December ruling from the Swedish Migration Court of Appeal now required the Migration Agency to look at the entirety of an individual's case when making decisions, meaning small administrative errors should not result in deportations.

But, as Alnomany's case and many others make clear, skilled workers and entrepreneurs are still being forced to leave Sweden.

"It depends on what you classify as a small mistake," Alnomany said of the agency's new legal framework. "Maybe not taking a salary is not a small mistake."

The entrepreneur said he would now try to appeal the ruling once again, but described his chances of success as "really slim".

"It's not Migrationsverket's fault. They're just applying the rules blindly, so we just need to put some momentum so people can say maybe these rules need to be changed," he said.

"However, I believe that this is an injustice, so I need to fight it to the end and see where it goes."

He said it was particularly frustrating that the ruling had come at a time when the company he co-founded along with was looking increasingly close to becoming profitable.

"Right now we are making progress. Right now we are in a partnership with a Japanese company and starting to sell all over the world," he said. "It took a lot of effort to secure that partnership, and bear in mind that I was locked in the country. I can't go and meet them there. I had to bring their team, their president, here."

With both Alnomany and his co-founder Pau Mallol now well established in Sweden and the company growing fast, he said he still hoped to stay in the country somehow.

"There's not many companies in the world who are doing such things. It's deep tech. I really want to keep it in Swedish borders so that the wider community can benefit," he said.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.