Why a Swedish gift to Barcelona is still causing a fuss 90 years later

Why did a wooden tower made in Uppsala, Sweden, travel thousands of kilometres by boat to Barcelona in the 1920s? And why is it still causing a fuss almost 90 years later?

The story of the Sweden Tower (La Torre de Suècia) is a fascinating one full of twists and turns, yet one that is also almost unknown in Barcelona, let alone back in Sweden.

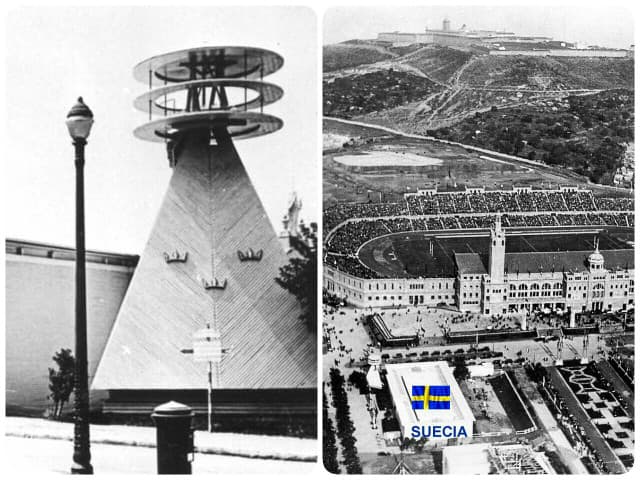

The wooden structure was designed by Swedish architect Peder Clason in order to show off Swedish design at the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. Built in Örbyhus, Uppsala, in 1928, it was sent in pieces along with an accompanying pavilion via boat to Catalonia and erected outside the main entrance to the Montjuïc stadium.

It's what happened in the years that followed that makes the Sweden Tower particularly interesting. Ever the altruists even back then, when the exposition was over, Sweden agreed to give the structure to the city of Barcelona on the sole condition that it was used for social causes.

The pavilion was subsequently moved to the smaller city of Berga, north of Barcelona, where it was inaugurated by iconic Catalan President Lluís Companys and used as a school for girls from poor families from 1932 onwards. In a letter written by one of former students, María de la Torre, the school was described as one where the education was "in no way elitist. It was universal, free, secular and without cost. If I could I would go back".

Jairo Narváez, head of the Friends of the Sweden Tower association (Associació d'Amics de la Torre Suècia), explains to The Local that the school was unlike any in the country at the time:

"The then King of Sweden was a tennis fanatic, for example. And the girls at the school were taught how to play tennis. They were sent equipment. That was unthinkable for poor kids in Barcelona at the time. Tennis was a very elitist sport, only the wealthy here played it. Poor girls from Barcelona? No chance."

That Sweden-inspired idealism would only last for a few years however, as in 1936 the Spanish Civil War kicked off, and necessities quickly changed. The wood from the tower was used as emergency fuel during the winters, while the pavilion was used by the military. Catalonia, part of the Republican side, lost the war and Franco's troops eventually had the building destroyed in 1962.

Jairo signing copies of a book he has written about the history of the tower. Photo: Jairo Narváez

Even then, the strange wooden structure hadn't seen its final days. Several decades after the end of the dictatorship in Spain, a movement to have the buildings restored started, and in 2008 the rebuilding of the pavilion in Berga was completed with the addition of a new tower, more than half a century after its destruction. Still, not everyone was happy.

The Friends of the Sweden Tower consider the new structure in Berga to be a poor imitation not faithful to the architecture of the original. The copy is not made with the correct materials and to the standards of the first, they argue. The mayor of Berga counters however that rebuilding the tower in the original manner wouldn't have made it sustainable for the future.

Narváez and his association are now pushing to have a new, more faithful tower built in the city where it originally stood, Barcelona. Moreover, he wants it to be built by Swedes.

"All the details need to be approved by various entities including the Catalan Government and City Council in order to build something at Montjuïc," he explains. "But that's a process, and what we're doing right now is trying to inform people."

In the meantime, the association has recently opened an exhibition near the original Montjuïc site of the first tower explaining its history through images and documents.

"Practically all the documents and photographs I have from years of investigation came from Sweden's archives. They helped me to bring all of this to light," he notes.

The new exhibition on the tower in Montjuïc. Photo: Jairo Narváez

Now, locals and tourists alike can learn about the unknown link between the Nordic country and the Catalan capital. That's more than worth the effort, according to Narváez.

"When Swedes climb the mountain and see the flag here, then hear the story, they're delighted. They learn something about their own culture they never knew about. We're not going to get rich from this, but we're happy!”

Comments

See Also

The story of the Sweden Tower (La Torre de Suècia) is a fascinating one full of twists and turns, yet one that is also almost unknown in Barcelona, let alone back in Sweden.

The wooden structure was designed by Swedish architect Peder Clason in order to show off Swedish design at the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. Built in Örbyhus, Uppsala, in 1928, it was sent in pieces along with an accompanying pavilion via boat to Catalonia and erected outside the main entrance to the Montjuïc stadium.

It's what happened in the years that followed that makes the Sweden Tower particularly interesting. Ever the altruists even back then, when the exposition was over, Sweden agreed to give the structure to the city of Barcelona on the sole condition that it was used for social causes.

The pavilion was subsequently moved to the smaller city of Berga, north of Barcelona, where it was inaugurated by iconic Catalan President Lluís Companys and used as a school for girls from poor families from 1932 onwards. In a letter written by one of former students, María de la Torre, the school was described as one where the education was "in no way elitist. It was universal, free, secular and without cost. If I could I would go back".

Jairo Narváez, head of the Friends of the Sweden Tower association (Associació d'Amics de la Torre Suècia), explains to The Local that the school was unlike any in the country at the time:

"The then King of Sweden was a tennis fanatic, for example. And the girls at the school were taught how to play tennis. They were sent equipment. That was unthinkable for poor kids in Barcelona at the time. Tennis was a very elitist sport, only the wealthy here played it. Poor girls from Barcelona? No chance."

That Sweden-inspired idealism would only last for a few years however, as in 1936 the Spanish Civil War kicked off, and necessities quickly changed. The wood from the tower was used as emergency fuel during the winters, while the pavilion was used by the military. Catalonia, part of the Republican side, lost the war and Franco's troops eventually had the building destroyed in 1962.

Jairo signing copies of a book he has written about the history of the tower. Photo: Jairo Narváez

Even then, the strange wooden structure hadn't seen its final days. Several decades after the end of the dictatorship in Spain, a movement to have the buildings restored started, and in 2008 the rebuilding of the pavilion in Berga was completed with the addition of a new tower, more than half a century after its destruction. Still, not everyone was happy.

The Friends of the Sweden Tower consider the new structure in Berga to be a poor imitation not faithful to the architecture of the original. The copy is not made with the correct materials and to the standards of the first, they argue. The mayor of Berga counters however that rebuilding the tower in the original manner wouldn't have made it sustainable for the future.

Narváez and his association are now pushing to have a new, more faithful tower built in the city where it originally stood, Barcelona. Moreover, he wants it to be built by Swedes.

"All the details need to be approved by various entities including the Catalan Government and City Council in order to build something at Montjuïc," he explains. "But that's a process, and what we're doing right now is trying to inform people."

In the meantime, the association has recently opened an exhibition near the original Montjuïc site of the first tower explaining its history through images and documents.

"Practically all the documents and photographs I have from years of investigation came from Sweden's archives. They helped me to bring all of this to light," he notes.

The new exhibition on the tower in Montjuïc. Photo: Jairo Narváez

Now, locals and tourists alike can learn about the unknown link between the Nordic country and the Catalan capital. That's more than worth the effort, according to Narváez.

"When Swedes climb the mountain and see the flag here, then hear the story, they're delighted. They learn something about their own culture they never knew about. We're not going to get rich from this, but we're happy!”

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.