How this Syrian escaped imprisonment and torture for a new life in Sweden

Now living a positive life in Sweden, Omar Alshogre spent three years detained without trial in Syria, suffering torture and inhumane treatment. He tells The Local contributor Jamil Walli about surviving the horrors of life in prison, and his plans for a new future in Stockholm.

Barrel bombs, chemical attacks, mass fatalities and mass displacement are a handful of the horrors that have shaped Syria’s reality throughout the last six years, silencing other, hardly seen terrors, committed day and night in Bashar al-Assad’s bleak prisons.

Thousands of Syrians are hitherto detained in prisons – seized into oblivion. How much do we know about them?

Omar Alshogre, 21, is one of those who lived in the regime’s dungeons and made it out alive, with heart-wrenching memories of fear and barbarity that are indescribable.

It was in the Damascus Branch 215 of the Military Intelligence Directorate, and Sednaya prison near the capital, where Alshogre spent three years for participating in his hometown's protests.

"Shortly after the Syrian revolution erupted in Dar'a in 2011, I and my cousins joined demonstrations marching on the streets of our village, Al-Bayda. I was arrested and freed several times before I was eventually kept underground," he describes.

On October 16th 2012, Alshorge was visiting his cousins when two armed militiamen invaded their house, and arrested everyone – Omar, his cousins, Rashad and Bashir, along with their sister Nour – before they were all sent to the Military Intelligence in central Tartus for investigation.

"We were put in solitary confinement for ten days, then into cells, and were investigated under torture. The tormenting was collective: they used to assemble us in groups of 15-20 detainees, all naked and blindfolded, before they’d start battering us indiscriminately with batons, screwdrivers, spades or anything they found that could excruciate us," he recalls.

"They burned our skin with cigarettes, and electrocuted our testicles – we whined, they laughed. They bathed us in boiling water followed by freezing water interchangeably, so we would jerk and be stunned."

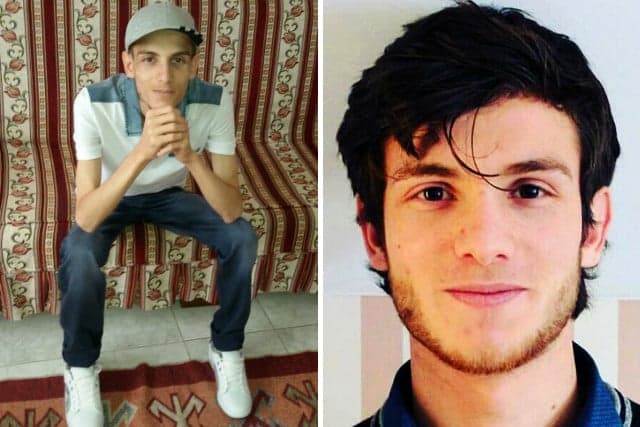

Alshogre pictured in Syria after his release. Photo: Omar Alshogre

The jailors wanted him to confess the type of weapons he had wielded and how many soldiers he had killed, recounts Omar:

"They wanted me to admit something, anything. Under torture I confessed that I and my mum were terrorists, that my sister owned a fighter jet, and that my dad was a ringleader. I confessed things that I had never imagined, just to convince them to let go of me – I was in pain."

Unfortunately, the young man didn’t realize that the torture he had witnessed in Tartus was a prelude to what would unfold a month later in Damascus.

"They told us our cases were transferred to Damascus, so long as the investigations went on, therefore we were sent to the capital. As I entered the large underground cell in Branch 215, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Prima facie, I thought I was hallucinating: 'what were those bodies?' I wondered. 'Were they human? Were they alive?' Lame humans barely moving. Deformed faces and bodies. Some had lost their limbs, some had bruised skin, others had their bodies crammed with maggots feeding on their inflated wounds. Those who didn't move were corpses – the place seemed like it had been stricken by a mythical plague, death was emanating from every corner," describes Alshogre.

He continues: "we were piled, 2500 detainees, into an underground cell that could hardly accommodate 500. We had to alternate between crouching down and standing up throughout the day and night."

His cousins were also sent to the same prison in Damascus. Rachad couldn’t survive the miserable conditions underground, and died in few weeks. Bashir grieved for his brother’s death, and his sister's imprisonment – she was in the women’s cell of the same branch upstairs – and spent a year starving himself to death. Bashir passed away in Omar's arms.

"Most prisoners abandoned the toilets, because, one would queue in line for at least eight hours and expect unbearable abuse from jailors, before at the end, the lucky inmate would have ten seconds to finish. If you got there, a jailor would wait for you outside the lavatory door and start counting: one, two, three, … nine. He'd yell: 'rinse your ar*****, ten,' he'd drag you from toilet like a dead body," he recounts.

"Prisoners preferred to wait for lunch time instead; they used bread bags and rice plates to discharge in them, collectively. We more than often got our meals mixed with our excrement."

It is difficult to imagine the health conditions underground. As Omar recalls, some prisoners stayed in their centimetres of space for months, where they had seen no sun light, plunging in squalor. Those who were wounded under torture, would later rot to death. The lucky ones, like Omar, survived.

Death was a requirement for the prison to keep running

"It took me time to comprehend that there had to be deaths on a daily basis; the death target was scheduled for weeks ahead. I remember, for example, in summertime 50 detainees had to die every day, and when 43 died on their own – that was habitual – jailors would come and cherry-pick seven inmates for their final fate, to reach their targeted number," asserts Alshogre.

"A 'doctor' was often borrowed from military hospital to inject the hapless detainees with air-filled syringes in their necks' carotid arteries, outside the cell. Or, jailors would command a random prisoner to slaughter fellow inmates they chose to be killed."

The corpses needed to be collected every day by dawn, to be later "thrown away" in the "disposal truck," as superintendents usually ordered.

Omar miraculously survived his year and nine months in Branch 215 despite its hellish nature. He even survived the moments when jailors had had manic episodes, rushing amok into the cell, slaughtering their way in and out, leaving carnage behind. He made friends with a few highly-experienced long-detained activists, who helped prevent his slaughter until he finally was moved to Sednaya prison – the worst of all.

Sednaya prison: "where God has no presence"

"On August 15th 2014 I was transferred to Sednaya prison, when I had turned 18. Before being sent to cells, all inmates were lined up naked in an open square to learn the rules. A jailor spoke loudly: 'welcome to Sednaya prison. Welcome to hell. God has no presence here, and all other gods never visit this place. There shall be no prayers, no fasting, and no piety – no voices shall be heard, neither muttering, nor hissing," Alshogre recites.

"Prison guards wielded strangely thick cudgels, or coarse whips, that were later known as 'tank tracks'. They asked if any inmates had diseases: those who were sick and raised their hands, were pulled from lines and battered to death. 'No illnesses were allowed' said jailors. Death was preferred for keeping the prison clean of an epidemic outbreak."

After indoctrination, Omar says, detainees were put in groups of eleven into makeshift dungeons that were no larger than two square metres, for eleven days. They were deprived of water, and it was also during the scorching summertime. As he puts it:

"We were heaped, sticking to each other, extremely tight, just like pickled cucumbers in a jar. On the seventh day some inmates started to piss and drink their own urine. Intoxication and thirst: detainees perished in tens."

On the 11th day the surviving detainees were transferred to larger cells, where they would stay thereafter. Alshogre was sent to the third floor in a big cell shared with other inmates. They had one meal a day that was mostly bloodied, and were strictly ordered to stay three metres away from the cell's door – otherwise, if breaching rules, inmates would’ve expected bloodshed.

For the first two months, Alshogre kept "pooping his pants" out of panic whenever jailors opened the cell door, because, as he describes it, guards visited cells either to bring inedible food, or, to commit crimes. The whole prison was in deafening silence at the times when there was no torture or howling, and under torment, the more inmates screamed, the more jailors would brutally ravage them. Squeaking enraged jailors.

Alshogre in Idlib, northwestern Syria after his release. Photo: Omar Alshogre

Omar embraced his fears until he was finally freed in June 2015, when his mum found out her son was alive as he bribed his way out through a broker in their town, who had forged contacts with Assad’s corrupt authorities.

Alshogre left detention with his dad massacred in 2013, his two cousins perished in front of his eyes, and himself contracting Tuberculosis. He left detention with memories of three years that are cruel enough to bring the bravest of people to their knees. He headed to Turkey to see his mum and heave a sigh of relief, before he finally moved to Sweden, sought treatment and started his life anew in December 2015.

"I didn't want to die; my instinct to live was mightier than all the horrors that I witnessed. Now I’m living the happiest days of my life. I now understand what does it mean to be free."

Now, Alshogre lives with a Swedish family in Stockholm and is still receiving treatment. He works as a substitute teacher after a spell at an amusement park, and has been granted a residence permit. When his Swedish ID arrives, his plan is to start advanced language courses before moving on to a university degree, either in civil engineering or journalism:

"I am living with a very passionate Swedish family in Nacka. I feel like I am living with my mum and dad – they opened their hearts to me. Now, my work helps me support my mum in Turkey. I hope, we’ll have the chance to reunite again."

Interview conducted and article written by The Local contributor Jamil Walli.

Comments

See Also

Barrel bombs, chemical attacks, mass fatalities and mass displacement are a handful of the horrors that have shaped Syria’s reality throughout the last six years, silencing other, hardly seen terrors, committed day and night in Bashar al-Assad’s bleak prisons.

Thousands of Syrians are hitherto detained in prisons – seized into oblivion. How much do we know about them?

Omar Alshogre, 21, is one of those who lived in the regime’s dungeons and made it out alive, with heart-wrenching memories of fear and barbarity that are indescribable.

It was in the Damascus Branch 215 of the Military Intelligence Directorate, and Sednaya prison near the capital, where Alshogre spent three years for participating in his hometown's protests.

"Shortly after the Syrian revolution erupted in Dar'a in 2011, I and my cousins joined demonstrations marching on the streets of our village, Al-Bayda. I was arrested and freed several times before I was eventually kept underground," he describes.

On October 16th 2012, Alshorge was visiting his cousins when two armed militiamen invaded their house, and arrested everyone – Omar, his cousins, Rashad and Bashir, along with their sister Nour – before they were all sent to the Military Intelligence in central Tartus for investigation.

"We were put in solitary confinement for ten days, then into cells, and were investigated under torture. The tormenting was collective: they used to assemble us in groups of 15-20 detainees, all naked and blindfolded, before they’d start battering us indiscriminately with batons, screwdrivers, spades or anything they found that could excruciate us," he recalls.

"They burned our skin with cigarettes, and electrocuted our testicles – we whined, they laughed. They bathed us in boiling water followed by freezing water interchangeably, so we would jerk and be stunned."

Alshogre pictured in Syria after his release. Photo: Omar Alshogre

The jailors wanted him to confess the type of weapons he had wielded and how many soldiers he had killed, recounts Omar:

"They wanted me to admit something, anything. Under torture I confessed that I and my mum were terrorists, that my sister owned a fighter jet, and that my dad was a ringleader. I confessed things that I had never imagined, just to convince them to let go of me – I was in pain."

Unfortunately, the young man didn’t realize that the torture he had witnessed in Tartus was a prelude to what would unfold a month later in Damascus.

"They told us our cases were transferred to Damascus, so long as the investigations went on, therefore we were sent to the capital. As I entered the large underground cell in Branch 215, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Prima facie, I thought I was hallucinating: 'what were those bodies?' I wondered. 'Were they human? Were they alive?' Lame humans barely moving. Deformed faces and bodies. Some had lost their limbs, some had bruised skin, others had their bodies crammed with maggots feeding on their inflated wounds. Those who didn't move were corpses – the place seemed like it had been stricken by a mythical plague, death was emanating from every corner," describes Alshogre.

He continues: "we were piled, 2500 detainees, into an underground cell that could hardly accommodate 500. We had to alternate between crouching down and standing up throughout the day and night."

His cousins were also sent to the same prison in Damascus. Rachad couldn’t survive the miserable conditions underground, and died in few weeks. Bashir grieved for his brother’s death, and his sister's imprisonment – she was in the women’s cell of the same branch upstairs – and spent a year starving himself to death. Bashir passed away in Omar's arms.

"Most prisoners abandoned the toilets, because, one would queue in line for at least eight hours and expect unbearable abuse from jailors, before at the end, the lucky inmate would have ten seconds to finish. If you got there, a jailor would wait for you outside the lavatory door and start counting: one, two, three, … nine. He'd yell: 'rinse your ar*****, ten,' he'd drag you from toilet like a dead body," he recounts.

"Prisoners preferred to wait for lunch time instead; they used bread bags and rice plates to discharge in them, collectively. We more than often got our meals mixed with our excrement."

It is difficult to imagine the health conditions underground. As Omar recalls, some prisoners stayed in their centimetres of space for months, where they had seen no sun light, plunging in squalor. Those who were wounded under torture, would later rot to death. The lucky ones, like Omar, survived.

Death was a requirement for the prison to keep running

"It took me time to comprehend that there had to be deaths on a daily basis; the death target was scheduled for weeks ahead. I remember, for example, in summertime 50 detainees had to die every day, and when 43 died on their own – that was habitual – jailors would come and cherry-pick seven inmates for their final fate, to reach their targeted number," asserts Alshogre.

"A 'doctor' was often borrowed from military hospital to inject the hapless detainees with air-filled syringes in their necks' carotid arteries, outside the cell. Or, jailors would command a random prisoner to slaughter fellow inmates they chose to be killed."

The corpses needed to be collected every day by dawn, to be later "thrown away" in the "disposal truck," as superintendents usually ordered.

Omar miraculously survived his year and nine months in Branch 215 despite its hellish nature. He even survived the moments when jailors had had manic episodes, rushing amok into the cell, slaughtering their way in and out, leaving carnage behind. He made friends with a few highly-experienced long-detained activists, who helped prevent his slaughter until he finally was moved to Sednaya prison – the worst of all.

Sednaya prison: "where God has no presence"

"On August 15th 2014 I was transferred to Sednaya prison, when I had turned 18. Before being sent to cells, all inmates were lined up naked in an open square to learn the rules. A jailor spoke loudly: 'welcome to Sednaya prison. Welcome to hell. God has no presence here, and all other gods never visit this place. There shall be no prayers, no fasting, and no piety – no voices shall be heard, neither muttering, nor hissing," Alshogre recites.

"Prison guards wielded strangely thick cudgels, or coarse whips, that were later known as 'tank tracks'. They asked if any inmates had diseases: those who were sick and raised their hands, were pulled from lines and battered to death. 'No illnesses were allowed' said jailors. Death was preferred for keeping the prison clean of an epidemic outbreak."

After indoctrination, Omar says, detainees were put in groups of eleven into makeshift dungeons that were no larger than two square metres, for eleven days. They were deprived of water, and it was also during the scorching summertime. As he puts it:

"We were heaped, sticking to each other, extremely tight, just like pickled cucumbers in a jar. On the seventh day some inmates started to piss and drink their own urine. Intoxication and thirst: detainees perished in tens."

On the 11th day the surviving detainees were transferred to larger cells, where they would stay thereafter. Alshogre was sent to the third floor in a big cell shared with other inmates. They had one meal a day that was mostly bloodied, and were strictly ordered to stay three metres away from the cell's door – otherwise, if breaching rules, inmates would’ve expected bloodshed.

For the first two months, Alshogre kept "pooping his pants" out of panic whenever jailors opened the cell door, because, as he describes it, guards visited cells either to bring inedible food, or, to commit crimes. The whole prison was in deafening silence at the times when there was no torture or howling, and under torment, the more inmates screamed, the more jailors would brutally ravage them. Squeaking enraged jailors.

Alshogre in Idlib, northwestern Syria after his release. Photo: Omar Alshogre

Omar embraced his fears until he was finally freed in June 2015, when his mum found out her son was alive as he bribed his way out through a broker in their town, who had forged contacts with Assad’s corrupt authorities.

Alshogre left detention with his dad massacred in 2013, his two cousins perished in front of his eyes, and himself contracting Tuberculosis. He left detention with memories of three years that are cruel enough to bring the bravest of people to their knees. He headed to Turkey to see his mum and heave a sigh of relief, before he finally moved to Sweden, sought treatment and started his life anew in December 2015.

"I didn't want to die; my instinct to live was mightier than all the horrors that I witnessed. Now I’m living the happiest days of my life. I now understand what does it mean to be free."

Now, Alshogre lives with a Swedish family in Stockholm and is still receiving treatment. He works as a substitute teacher after a spell at an amusement park, and has been granted a residence permit. When his Swedish ID arrives, his plan is to start advanced language courses before moving on to a university degree, either in civil engineering or journalism:

"I am living with a very passionate Swedish family in Nacka. I feel like I am living with my mum and dad – they opened their hearts to me. Now, my work helps me support my mum in Turkey. I hope, we’ll have the chance to reunite again."

Interview conducted and article written by The Local contributor Jamil Walli.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.