'I'm leaving for the West, who's coming?'

There are many of tales of ingenious and well-thought out escape plans from people desperate to flee from East to West Berlin. Wolfgang Engels’ wasn’t one of them. It was, however, one of the most daring.

Engels’ plan to flee East Germany 51 years ago was simple: Step 1 - Steal an armoured car; Step 2 - Point it at the Berlin Wall; Step 3 - Step on the gas - and crash through.

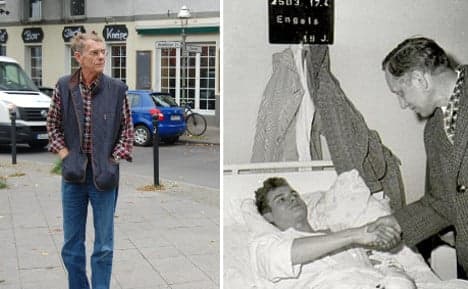

He made it, just, but was shot twice before he could ask for a cognac in the safety of a West Berlin bar on April 16th 1963. Now 71, the escapee revisited the spot with The Local to mark 25 years since the Wall fell.

“I’m getting out of here to the West, anyone want to come along?” the teenager shouted over the roar of the nine-ton vehicle’s engine to some youths standing by the road near the Wall.

No one did, unsurprisingly, since most people considered trying to escape East Germany (the GDR) an act of madness, punishable by at least two years in jail or death from the border guards’ rifles.

So Wolfgang Engels, a 19-year-old civilian driver working for the East German army, gunned the motor and set a ramming course for the American sector.

A Stasi mother

His escape was no long-harboured plan born of ideological disillusionment. “I had a thorough socialist upbringing,” Engels says, although he acknowledges a change in his perspective around the time of his escape following conversations with a critic of the system.

He could possibly even have fled two years earlier when he was sent to East Berlin as a soldier during the initial construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

But the decision resulted more from anger at how he and two friends were treated by security forces - and family - a few weeks earlier while looking for a concert in a cafe near the Wall.

They were detained and accused of Republikflucht, attempting to escape. It was their genuine indignation and the fact they were dressed for an evening out that saved them from prosecution.

The three were released but Engels received little sympathy from his mother, who unbeknownst to him was an administrative worker for the Staatssicherheitsdienst, the Stasi secret police. She fully agreed with the way they had been treated.

“That’s what shocked me, that a person can adhere so firmly to the idea that ‘the Party is always right’,” said Engels. “So I told myself that I would take the very next chance to get out of here.”

That chance came a few days before the annual May 1st parade, when the car he chauffeured army officials with was parked with a batch of new armoured personnel carriers.

The escape

He quickly hatched his plan, befriended the army drivers and let them take his vehicle for a spin. In return they showed him their PSW 152 six-wheelers and told him how they work.

Confident he could handle one, Engels waited until the crews went to eat and helped himself to a brand new getaway vehicle.

The city was full of military traffic at the time. One more vehicle drew little attention as he motored east down Stalin Allee in the early evening, crossed the Spree River into Treptow and towards his target stretch of the Wall.

After offering the bystanders a rider – an excited impulse as he hopped out to secure the rear hatch - he revved the engine and sped off down the last 100-metre stretch.

But despite the vehicle’s momentum, it couldn’t break clean through the Wall, which in 1963 was still a single layered block construction standing almost three metres high.

Low layers of additional concrete barriers and dense wire caused the vehicle to stall at the critical moment. Its nose punched through but the doors were still on the wrong side.

Engels climbed out and became ensnared in the barbed wire on the crest of the Wall. Seeing East German border guard Paul H. taking aim with his rifle just five metres away, he called out “Don’t shoot”. The guard shot anyway.

“The bullet went into my back and out of my front,” said Engels, who managed to get back inside the vehicle and exit the passenger door. “Then I was hit again, a ricochet this time that came so close that the splinters hit me in the hand.”

Fortunately for the escapee, stray rounds and stone fragments also came close to West German police watching the drama from a platform, allowing them to return fire and cover him.

Border bar

While the East Germans ducked, a group of men holding a drinking session in a bar on the West side rushed out and formed a human ladder to free him from the wire. The owner and guests quickly rolled down the shutters and laid the heavily bleeding youth on the counter.

“Half of them were plastered … But if they hadn’t been having a booze-up I’d never have made it,” Engels said.“I knew I was safe when I saw the western spirits bottles on the shelves.”

“The first thing he said was to give him a cognac or a beer,” one of his rescuers told US media the next day. Fortunately for Engels he was not given any alcohol, which would have thinned his blood and accelerated its loss.

Since the front façade of the bar was the actual border, paramedics came via the back of the building to evacuate him to hospital, where he spent three weeks recovering from a collapsed lung.

The Stasi report from the time reads: "Serious border breakthrough with an armoured personnel carrier.The post commander assumed it was a reinforcement of border security".

Rebuilding

Engels then went to see relatives in Düsseldorf where he was born and lived for ten years until his mother, a staunch member of the Communist Party, took him to live in East Germany. After his escape his mother formally disowned him in a statement. All mail he later sent to his mother and step-father was handed directly to the Stasi, while any phone calls immediately ended with a click of the handset.The next time they met was in 1990 after all charges were dropped against GDR escapees.

“My mother was happy enough to see me but we simply didn’t talk about what happened,” said Engels, who as well as learning about his mother’s Stasi past also discovered only later that East Germany still planned to abduct him to face desertion charges in the 1980s.

He never met the soldier who shot him, although he expected to in 1990 when the man was tried and acquitted in a spate of criminal cases against guards who fired on escapees.

But he harbours no bitterness and is still grateful that the soldier kept his rifle on single round mode rather than using bursts: “It says something for him that he didn’t use automatic fire. It just needed a hand motion, a click on his Kalashnikov.”

After a stint working in a British hotel, Engels retrained as a teacher and also served in the fire brigade for 20 years before retiring. Married with a daughter and three grandchildren, he now works for a Holocaust site preservation organization.

“I have no regrets,” he says of his flight to the West. “It was hard at the beginning but I have had a good life here.”

Special thanks to Dr Hans-Hermann Hertle of the Potsdam Centre for Research into Contemporary History for providing additional material.

Do you have memories of the Berlin Wall you'd like to share? Email [email protected]

By Nick Allen

SEE ALSO: How Berlin has changed in 22 photos

Comments (1)

See Also

Engels’ plan to flee East Germany 51 years ago was simple: Step 1 - Steal an armoured car; Step 2 - Point it at the Berlin Wall; Step 3 - Step on the gas - and crash through.

He made it, just, but was shot twice before he could ask for a cognac in the safety of a West Berlin bar on April 16th 1963. Now 71, the escapee revisited the spot with The Local to mark 25 years since the Wall fell.

“I’m getting out of here to the West, anyone want to come along?” the teenager shouted over the roar of the nine-ton vehicle’s engine to some youths standing by the road near the Wall.

No one did, unsurprisingly, since most people considered trying to escape East Germany (the GDR) an act of madness, punishable by at least two years in jail or death from the border guards’ rifles.

So Wolfgang Engels, a 19-year-old civilian driver working for the East German army, gunned the motor and set a ramming course for the American sector.

A Stasi mother

His escape was no long-harboured plan born of ideological disillusionment. “I had a thorough socialist upbringing,” Engels says, although he acknowledges a change in his perspective around the time of his escape following conversations with a critic of the system.

He could possibly even have fled two years earlier when he was sent to East Berlin as a soldier during the initial construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

But the decision resulted more from anger at how he and two friends were treated by security forces - and family - a few weeks earlier while looking for a concert in a cafe near the Wall.

They were detained and accused of Republikflucht, attempting to escape. It was their genuine indignation and the fact they were dressed for an evening out that saved them from prosecution.

The three were released but Engels received little sympathy from his mother, who unbeknownst to him was an administrative worker for the Staatssicherheitsdienst, the Stasi secret police. She fully agreed with the way they had been treated.

“That’s what shocked me, that a person can adhere so firmly to the idea that ‘the Party is always right’,” said Engels. “So I told myself that I would take the very next chance to get out of here.”

That chance came a few days before the annual May 1st parade, when the car he chauffeured army officials with was parked with a batch of new armoured personnel carriers.

The escape

He quickly hatched his plan, befriended the army drivers and let them take his vehicle for a spin. In return they showed him their PSW 152 six-wheelers and told him how they work.

Confident he could handle one, Engels waited until the crews went to eat and helped himself to a brand new getaway vehicle.

The city was full of military traffic at the time. One more vehicle drew little attention as he motored east down Stalin Allee in the early evening, crossed the Spree River into Treptow and towards his target stretch of the Wall.

After offering the bystanders a rider – an excited impulse as he hopped out to secure the rear hatch - he revved the engine and sped off down the last 100-metre stretch.

But despite the vehicle’s momentum, it couldn’t break clean through the Wall, which in 1963 was still a single layered block construction standing almost three metres high.

Low layers of additional concrete barriers and dense wire caused the vehicle to stall at the critical moment. Its nose punched through but the doors were still on the wrong side.

Engels climbed out and became ensnared in the barbed wire on the crest of the Wall. Seeing East German border guard Paul H. taking aim with his rifle just five metres away, he called out “Don’t shoot”. The guard shot anyway.

“The bullet went into my back and out of my front,” said Engels, who managed to get back inside the vehicle and exit the passenger door. “Then I was hit again, a ricochet this time that came so close that the splinters hit me in the hand.”

Fortunately for the escapee, stray rounds and stone fragments also came close to West German police watching the drama from a platform, allowing them to return fire and cover him.

Border bar

While the East Germans ducked, a group of men holding a drinking session in a bar on the West side rushed out and formed a human ladder to free him from the wire. The owner and guests quickly rolled down the shutters and laid the heavily bleeding youth on the counter.

“Half of them were plastered … But if they hadn’t been having a booze-up I’d never have made it,” Engels said.“I knew I was safe when I saw the western spirits bottles on the shelves.”

“The first thing he said was to give him a cognac or a beer,” one of his rescuers told US media the next day. Fortunately for Engels he was not given any alcohol, which would have thinned his blood and accelerated its loss.

Since the front façade of the bar was the actual border, paramedics came via the back of the building to evacuate him to hospital, where he spent three weeks recovering from a collapsed lung.

The Stasi report from the time reads: "Serious border breakthrough with an armoured personnel carrier.The post commander assumed it was a reinforcement of border security".

Rebuilding

After his escape his mother formally disowned him in a statement. All mail he later sent to his mother and step-father was handed directly to the Stasi, while any phone calls immediately ended with a click of the handset.The next time they met was in 1990 after all charges were dropped against GDR escapees.

“My mother was happy enough to see me but we simply didn’t talk about what happened,” said Engels, who as well as learning about his mother’s Stasi past also discovered only later that East Germany still planned to abduct him to face desertion charges in the 1980s.

He never met the soldier who shot him, although he expected to in 1990 when the man was tried and acquitted in a spate of criminal cases against guards who fired on escapees.

But he harbours no bitterness and is still grateful that the soldier kept his rifle on single round mode rather than using bursts: “It says something for him that he didn’t use automatic fire. It just needed a hand motion, a click on his Kalashnikov.”

After a stint working in a British hotel, Engels retrained as a teacher and also served in the fire brigade for 20 years before retiring. Married with a daughter and three grandchildren, he now works for a Holocaust site preservation organization.

“I have no regrets,” he says of his flight to the West. “It was hard at the beginning but I have had a good life here.”

Special thanks to Dr Hans-Hermann Hertle of the Potsdam Centre for Research into Contemporary History for providing additional material.

Do you have memories of the Berlin Wall you'd like to share? Email [email protected]

By Nick Allen

SEE ALSO: How Berlin has changed in 22 photos

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.