Stalingrad, the Nazis and Sweden: An Xmas story

Contributor Nick Walker tells the story of a Swedish artist's swastika Christmas card sent to ring in 1944 and the unlikely journey that it has taken over the last six decades.

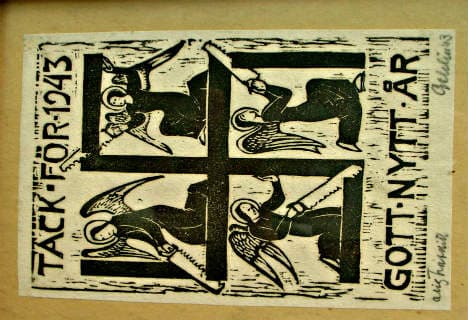

Four angels destroying a Nazi swastika. I love this image. It’s close to my heart. It’s also an artefact that is a witness to the most epic period of European history, as viewed from Sweden – specifically Helsingborg.

With the recently-released Russian movie Stalingrad suddenly capturing the world’s attention, I'm again reminded of this Swedish wartime artwork that has survived the decades since, and made an extraordinary journey around the world.

Indeed, it’s a piece of art that would likely never have been created had the battle of Stalingrad proved to be the turning point of World War II. It’s actually a simple New Year’s greeting card but one with a remarkable narrative.

When Nazi forces surrendered at Stalingrad in February 1943, the tide of the war had turned. Throughout 1943 enough information filtered out from the Eastern Front to the outside world for a dawning of the realization that the Third Reich was doomed.

While Sweden remained officially neutral during the conflict, many Swedes nevertheless were left disgusted by Nazism.

One nationally renowned-artist was particularly appalled. His name was Hugo Gehlin, who, during WWII, lived in the southern Swedish city of Helsingborg. At this time in his life he was a rather overweight bald 50-something, known as a garrulous socialite with a large network of friends and admirers.

He was also a creature of habit, and every year he printed up a limited edition of about 600 Christmas cards that traditionally featured a topical woodblock. This was what he sent out to friends, family, and people in the arts scene in which he frequented.

No Christmas card he put in the mail was more memorable than that which he created for 1944, whose text simply read: “Thank you for 1943” and “Happy New Year."

It featured four angels sawing up a swastika, the demise of Nazism having become apparent over 1943, a process that began in Stalingrad (now named Volgograd).

Gehlin was evidently unaware that his intended Nazi swastika was in fact a Buddhist symbol (Nazi swastikas are 'tilted', they do not lie flat with a vertical axis), but its message – the inevitability of the triumph of good over evil – was most welcome at a time when evil had been triumphing over good for too long.

This particular card in my possession was sent to a good friend of Hugo Gehlin’s – my late grandfather - Gustaf Lindgren. He was an art historian who in 1943 worked at the Waldemarsudde mansion of the arts as the personal secretary of Prince Eugén, fourth in line to the Swedish throne and known as “the Painter Prince."

After this woodblock print was placed in a drawer in my grandparents’ Djurgården home, probably sometime in early 1944, it was forgotten until resurfacing unexpectedly so many decades later in the 21st Century.

When my grandfather died in 1989, the card – one item in a large cache of papers and memorabilia – became property of his widow, my grandmother, Carin. When she passed away in Stockholm in 2001, the artwork ended up in a cardboard box that served as a receptacle for unwanted items and rubbish uncovered as family members cleaned up the house and made preparations for Carin’s funeral.

When this artefact caught my eye, amid broken crockery and withered potted plants, I swiftly rescued it and began researching its history. Gehlin died in 1953 but I was fortunate enough to speak with his son, Jan Gehlin, less than a year before he died at the age of 88 in 2010.

At that time, he was living in central Stockholm and shared his vivid memories of the time when the family home in Helsingborg was a sanctuary for Jews fleeing from Denmark.

“My father was a courageous and principled man, and, despite his natural modesty, was proud of his actions during the war,” Jan Gehlin told me.

The elder Gehlin evidently passed the torch of a brightly burning social conscience to Jan, who, in the view of Sweden’s post-war media, nobly upheld his father ideals both as a left-leaning novelist and a staunch trade unionist who served as president of the Swedish Writers’ Union (Sveriges Författarförbund) and its predecessor from 1965 to 1982.

“My father passed on his world view to me. We were very close as father and son. He was a passionate man. He was passionate about his art and all his work. And he was an anti-fascist with a passion that never wavered, especially during the war. His anti-Nazism burned all the more ferociously because his wife – my mother – was Jewish," Jan Gehlin recalled.

Helsingborg, on Sweden's southwest coast, is the closest Swedish city to Denmark. During the autumn of 1943, Hugo Gehlin and his wife Esther – a famous artist herself of Danish-Swedish parentage – were two of many Helsingborg residents who actively participated in the evacuation of almost 8,000 Jews from Nazi-occupied Denmark.

The year he sent out the Christmas card now in my possession proved to be the year he played a role in saving most of Denmark’s Jews from Nazi death camps.

Over the course of several weeks during the autumn of 1943, the Gehlin home was refuge to a large number of Danish Jews making their way to safer parts of Sweden. Despite Sweden’s neutrality, the actions of activists like the Gehlins were still somewhat perilous.

“It was only as an adult researching his life that I realized how he truly never missed an opportunity to express – through his art and his words – what he felt had to be said. He was hugely protective of his right to say and do the right thing,” Jan Gehlin said of his father.

The half-Jewish Jan joined his father in speaking out. And, like his father, he let his work do the talking. He was only 21 when he published his first collection of poems, also in that pivotal year, 1943. The message of the collection, Att gripa varligt (To seize tenderly) was that society had a duty to stand up against anti-Semitic bigotry.

Jan Gehlin was also immersed in politics at an early age.

“My father was a very friendly and very open man. We often had visitors in the house. And the talk always quickly turned political. It was my upbringing,” he said.

When I asked him about the poem on the back of the angel-swastika print made by his father, he offered some insight on Hugo Gehlin's intended message with the card.

“Because it featured a swastika, my father was concerned that the card would be misinterpreted, and so he asked one of his best friends, a conspicuously Jewish personality – and at that time one of Sweden's most internationally renowned painters – Isaac Grünewald, to pen a poem about the four angels featured in the woodcut.

Mr. Grünewald was happy to oblige," he recalled.

Isaac Grünewald was one of the most famous Jewish Swedes of his day, but died at the age of 57 in a plane crash only three years after he wrote the poem. He had led a remarkable life. A native Stockholmer, at the age of 19 Grünewald travelled to Paris to study art under painter legend Henri Matisse.

Grünewald regularly exhibited at home and abroad and art historians now often cite him as being responsible for introducing modernism to Sweden.

Hugo Gehlin died only six years after Grünewald of a heart attack. But he had already shaped the next generation of politically active Gehlins.

“Fascism cannot be compromised with. Have you been to Poland, have you seen Auschwitz?” the younger Gehlin asked, speaking with the clarity and passion of a man fifty years younger.

“We have a real duty to remember and to tell. And to preserve the truth, no matter how painful it is, in the interests of peace, freedom and for our own sons and daughters.”

And this sentiment is precisely why a Christmas card sent to my grandfather 70 years ago, holds so much meaning for me.

Lost for decades, and then chucked in a box of rubbish destined for some landfill, this unlikely witness of history managed to defeat capricious fate and the vicissitudes of generational change – and survive to tell its story.

Today the artwork occupies a place on one of the walls of my home in Phuket, Thailand, on an island that greets almost 100,000 Swedish tourists every year and is home to hundreds of Swedish residents. And whenever a guest – Swedish or otherwise – asks about the 70-year-old framed card on the wall, they get a history lesson.

Comments

See Also

Four angels destroying a Nazi swastika. I love this image. It’s close to my heart. It’s also an artefact that is a witness to the most epic period of European history, as viewed from Sweden – specifically Helsingborg.

With the recently-released Russian movie Stalingrad suddenly capturing the world’s attention, I'm again reminded of this Swedish wartime artwork that has survived the decades since, and made an extraordinary journey around the world.

Indeed, it’s a piece of art that would likely never have been created had the battle of Stalingrad proved to be the turning point of World War II. It’s actually a simple New Year’s greeting card but one with a remarkable narrative.

When Nazi forces surrendered at Stalingrad in February 1943, the tide of the war had turned. Throughout 1943 enough information filtered out from the Eastern Front to the outside world for a dawning of the realization that the Third Reich was doomed.

While Sweden remained officially neutral during the conflict, many Swedes nevertheless were left disgusted by Nazism.

One nationally renowned-artist was particularly appalled. His name was Hugo Gehlin, who, during WWII, lived in the southern Swedish city of Helsingborg. At this time in his life he was a rather overweight bald 50-something, known as a garrulous socialite with a large network of friends and admirers.

He was also a creature of habit, and every year he printed up a limited edition of about 600 Christmas cards that traditionally featured a topical woodblock. This was what he sent out to friends, family, and people in the arts scene in which he frequented.

No Christmas card he put in the mail was more memorable than that which he created for 1944, whose text simply read: “Thank you for 1943” and “Happy New Year."

It featured four angels sawing up a swastika, the demise of Nazism having become apparent over 1943, a process that began in Stalingrad (now named Volgograd).

Gehlin was evidently unaware that his intended Nazi swastika was in fact a Buddhist symbol (Nazi swastikas are 'tilted', they do not lie flat with a vertical axis), but its message – the inevitability of the triumph of good over evil – was most welcome at a time when evil had been triumphing over good for too long.

This particular card in my possession was sent to a good friend of Hugo Gehlin’s – my late grandfather - Gustaf Lindgren. He was an art historian who in 1943 worked at the Waldemarsudde mansion of the arts as the personal secretary of Prince Eugén, fourth in line to the Swedish throne and known as “the Painter Prince."

After this woodblock print was placed in a drawer in my grandparents’ Djurgården home, probably sometime in early 1944, it was forgotten until resurfacing unexpectedly so many decades later in the 21st Century.

When my grandfather died in 1989, the card – one item in a large cache of papers and memorabilia – became property of his widow, my grandmother, Carin. When she passed away in Stockholm in 2001, the artwork ended up in a cardboard box that served as a receptacle for unwanted items and rubbish uncovered as family members cleaned up the house and made preparations for Carin’s funeral.

When this artefact caught my eye, amid broken crockery and withered potted plants, I swiftly rescued it and began researching its history. Gehlin died in 1953 but I was fortunate enough to speak with his son, Jan Gehlin, less than a year before he died at the age of 88 in 2010.

At that time, he was living in central Stockholm and shared his vivid memories of the time when the family home in Helsingborg was a sanctuary for Jews fleeing from Denmark.

“My father was a courageous and principled man, and, despite his natural modesty, was proud of his actions during the war,” Jan Gehlin told me.

The elder Gehlin evidently passed the torch of a brightly burning social conscience to Jan, who, in the view of Sweden’s post-war media, nobly upheld his father ideals both as a left-leaning novelist and a staunch trade unionist who served as president of the Swedish Writers’ Union (Sveriges Författarförbund) and its predecessor from 1965 to 1982.

“My father passed on his world view to me. We were very close as father and son. He was a passionate man. He was passionate about his art and all his work. And he was an anti-fascist with a passion that never wavered, especially during the war. His anti-Nazism burned all the more ferociously because his wife – my mother – was Jewish," Jan Gehlin recalled.

Helsingborg, on Sweden's southwest coast, is the closest Swedish city to Denmark. During the autumn of 1943, Hugo Gehlin and his wife Esther – a famous artist herself of Danish-Swedish parentage – were two of many Helsingborg residents who actively participated in the evacuation of almost 8,000 Jews from Nazi-occupied Denmark.

The year he sent out the Christmas card now in my possession proved to be the year he played a role in saving most of Denmark’s Jews from Nazi death camps.

Over the course of several weeks during the autumn of 1943, the Gehlin home was refuge to a large number of Danish Jews making their way to safer parts of Sweden. Despite Sweden’s neutrality, the actions of activists like the Gehlins were still somewhat perilous.

“It was only as an adult researching his life that I realized how he truly never missed an opportunity to express – through his art and his words – what he felt had to be said. He was hugely protective of his right to say and do the right thing,” Jan Gehlin said of his father.

The half-Jewish Jan joined his father in speaking out. And, like his father, he let his work do the talking. He was only 21 when he published his first collection of poems, also in that pivotal year, 1943. The message of the collection, Att gripa varligt (To seize tenderly) was that society had a duty to stand up against anti-Semitic bigotry.

Jan Gehlin was also immersed in politics at an early age.

“My father was a very friendly and very open man. We often had visitors in the house. And the talk always quickly turned political. It was my upbringing,” he said.

When I asked him about the poem on the back of the angel-swastika print made by his father, he offered some insight on Hugo Gehlin's intended message with the card.

“Because it featured a swastika, my father was concerned that the card would be misinterpreted, and so he asked one of his best friends, a conspicuously Jewish personality – and at that time one of Sweden's most internationally renowned painters – Isaac Grünewald, to pen a poem about the four angels featured in the woodcut.

Mr. Grünewald was happy to oblige," he recalled.

Isaac Grünewald was one of the most famous Jewish Swedes of his day, but died at the age of 57 in a plane crash only three years after he wrote the poem. He had led a remarkable life. A native Stockholmer, at the age of 19 Grünewald travelled to Paris to study art under painter legend Henri Matisse.

Grünewald regularly exhibited at home and abroad and art historians now often cite him as being responsible for introducing modernism to Sweden.

Hugo Gehlin died only six years after Grünewald of a heart attack. But he had already shaped the next generation of politically active Gehlins.

“Fascism cannot be compromised with. Have you been to Poland, have you seen Auschwitz?” the younger Gehlin asked, speaking with the clarity and passion of a man fifty years younger.

“We have a real duty to remember and to tell. And to preserve the truth, no matter how painful it is, in the interests of peace, freedom and for our own sons and daughters.”

And this sentiment is precisely why a Christmas card sent to my grandfather 70 years ago, holds so much meaning for me.

Lost for decades, and then chucked in a box of rubbish destined for some landfill, this unlikely witness of history managed to defeat capricious fate and the vicissitudes of generational change – and survive to tell its story.

Today the artwork occupies a place on one of the walls of my home in Phuket, Thailand, on an island that greets almost 100,000 Swedish tourists every year and is home to hundreds of Swedish residents. And whenever a guest – Swedish or otherwise – asks about the 70-year-old framed card on the wall, they get a history lesson.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.