'Good scientists aren't always that clever'

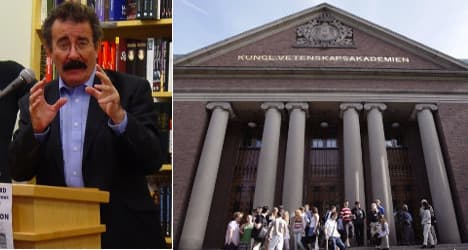

You don’t need to be a genius to aspire towards a Nobel Prize, British scientist professor Lord Robert Winston tells The Local. On Friday, the IVF pioneer will be in Stockholm, where he hopes to inspire the next generation of Nobel Laureates.

Two months ago, the world’s media flocked to Stockholm for the annual Nobel Prize announcements. Next week it's the turn of the winners themselves to pack their white ties and tiaras and head to the Swedish capital to receive their awards.

The Nobel Prizes reward the peak of human achievement in science, economics or literature, and are usually given many years after the work was carried out. Indeed, prize winners are often in their eighties. So how do we go about inspiring the next generation of laureates?

This Friday, Professor Lord Robert Winston, a British IVF pioneer, television personality and professor at Imperial College London, will travel to Stockholm to attempt do just that at an event organized by the British Embassy.

Talking to The Local this week, the scientist said that the most important form of inspiration comes through teaching.

“We need to recognize that the most important profession in the world is the teacher. That’s how we will inspire the next generation – by having inspirational teachers who are able to create lessons with practical work, where children can explore using experimentation.”

Harking back to his youth, Winston fondly recalled various school field trips, including one spent both on a marine trawler and on the seashore.“Now, of course, those kind of trips are too expensive."

But he was full of praise for the Scandinavian education system, citing the results of the latest OECD Pisa report, which classed Scandinavian countries Finland and Denmark above the UK (although Sweden was below - a fact that has caused much soul-searching).

“What you’re doing in Scandinavia is rather better than what we are doing in Britain. Standards – especially in science – are high, and you seem to value your teachers more highly than we do [in the UK], certainly in Finland.”

Although he accepts that the Nobel Prize plays an important part in raising the public profile of science, he also has some reservations about it.

“Perhaps the problem with the Nobel Prize is that the way the prize is won or awarded may not reflect the entire body of work that’s led to the award.”

The risk, he believes, is that young people are misled into thinking that you need to be a genius in order to merit such an award.

“To my mind, that’s not true. I actually think that you can be a very good scientist and actually not be that clever – like myself.

“In fact, a good proportion of my [scientific] papers I won’t understand myself,” he admitted, “because a mathematician has written part of it. Good science and good scientific research is very much about having good relationships with a group of people in a laboratory.”

Speaking to delegates at the London International Youth Science Forum in London earlier this year, Winston confessed to having discriminated against job applicants with first class degrees. Those with lower marks made better employees and more rounded individuals, he claimed.

Gone are the days of the lone genius – such as Barthes, Beethoven or Schubert – slaving away in isolation, according to Winston.

“When we award Nobel Prizes, it’s important to point out that most of these are not [for] blinding flashes of inspiration or innovation.” In fact, he says, the full value of a particular discovery may not be fully understood until about 60 years later.

Peter Higgs, who was this year’s joint winner for the Nobel Prize for physics for the Higgs Boson particle, is a case in point. Although his theory was conceived back in the 1960s, it was not until 2012 that it was actually proven.

Young people would do well to learn from Higgs’ example, he said. The physicist famously made himself unreachable on the day of this year's Nobel announcements: “I do quite like the idea of Peter Higgs going off on a trip and ignoring phone calls – that’s the right sort of role model,” he said.

“The recognition of celebrity is transient, ephemeral and unimportant – but what he [Higgs] formulated, years before anyone was able to show it was even a possibility, makes him a role model.”

Back in the UK, Winston and his team are currently working on an experiment involving transgenic animals, by introducing genes into their own genome. This, he says, will have “important ethical implications long-term.”

Outside the laboratory, the professor is working towards improving science education for children in the UK by introducing children aged six and upwards into a university setting.

His trip to Stockholm this Friday won’t be his first to the Swedish capital. But he says he’s more familiar with Gothenburg and the north of Sweden – and admits he can even understand a bit of Swedish “when totally drunk”.

Professor Lord Robert Winston will be talking at a free event organized by the British Embassy in Stockholm this Friday at Konserthuset (Hötorget 8). Click here for more information.

Comments

See Also

Two months ago, the world’s media flocked to Stockholm for the annual Nobel Prize announcements. Next week it's the turn of the winners themselves to pack their white ties and tiaras and head to the Swedish capital to receive their awards.

The Nobel Prizes reward the peak of human achievement in science, economics or literature, and are usually given many years after the work was carried out. Indeed, prize winners are often in their eighties. So how do we go about inspiring the next generation of laureates?

This Friday, Professor Lord Robert Winston, a British IVF pioneer, television personality and professor at Imperial College London, will travel to Stockholm to attempt do just that at an event organized by the British Embassy.

Talking to The Local this week, the scientist said that the most important form of inspiration comes through teaching.

“We need to recognize that the most important profession in the world is the teacher. That’s how we will inspire the next generation – by having inspirational teachers who are able to create lessons with practical work, where children can explore using experimentation.”

Harking back to his youth, Winston fondly recalled various school field trips, including one spent both on a marine trawler and on the seashore.“Now, of course, those kind of trips are too expensive."

But he was full of praise for the Scandinavian education system, citing the results of the latest OECD Pisa report, which classed Scandinavian countries Finland and Denmark above the UK (although Sweden was below - a fact that has caused much soul-searching).

“What you’re doing in Scandinavia is rather better than what we are doing in Britain. Standards – especially in science – are high, and you seem to value your teachers more highly than we do [in the UK], certainly in Finland.”

Although he accepts that the Nobel Prize plays an important part in raising the public profile of science, he also has some reservations about it.

“Perhaps the problem with the Nobel Prize is that the way the prize is won or awarded may not reflect the entire body of work that’s led to the award.”

The risk, he believes, is that young people are misled into thinking that you need to be a genius in order to merit such an award.

“To my mind, that’s not true. I actually think that you can be a very good scientist and actually not be that clever – like myself.

“In fact, a good proportion of my [scientific] papers I won’t understand myself,” he admitted, “because a mathematician has written part of it. Good science and good scientific research is very much about having good relationships with a group of people in a laboratory.”

Speaking to delegates at the London International Youth Science Forum in London earlier this year, Winston confessed to having discriminated against job applicants with first class degrees. Those with lower marks made better employees and more rounded individuals, he claimed.

Gone are the days of the lone genius – such as Barthes, Beethoven or Schubert – slaving away in isolation, according to Winston.

“When we award Nobel Prizes, it’s important to point out that most of these are not [for] blinding flashes of inspiration or innovation.” In fact, he says, the full value of a particular discovery may not be fully understood until about 60 years later.

Peter Higgs, who was this year’s joint winner for the Nobel Prize for physics for the Higgs Boson particle, is a case in point. Although his theory was conceived back in the 1960s, it was not until 2012 that it was actually proven.

Young people would do well to learn from Higgs’ example, he said. The physicist famously made himself unreachable on the day of this year's Nobel announcements: “I do quite like the idea of Peter Higgs going off on a trip and ignoring phone calls – that’s the right sort of role model,” he said.

“The recognition of celebrity is transient, ephemeral and unimportant – but what he [Higgs] formulated, years before anyone was able to show it was even a possibility, makes him a role model.”

Back in the UK, Winston and his team are currently working on an experiment involving transgenic animals, by introducing genes into their own genome. This, he says, will have “important ethical implications long-term.”

Outside the laboratory, the professor is working towards improving science education for children in the UK by introducing children aged six and upwards into a university setting.

His trip to Stockholm this Friday won’t be his first to the Swedish capital. But he says he’s more familiar with Gothenburg and the north of Sweden – and admits he can even understand a bit of Swedish “when totally drunk”.

Professor Lord Robert Winston will be talking at a free event organized by the British Embassy in Stockholm this Friday at Konserthuset (Hötorget 8). Click here for more information.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.