How Bergman blazed a trail for Swedish film

How did a small country like Sweden come to produce so many brilliant film directors? In part, at least, because one particularly talented man led the way.

For a country with a relatively small population, Sweden regularly manages to punch above its weight in the world of culture. There is perhaps no better example of this than the film industry, and for that the Swedes have one person to thank more than most - Ingmar Bergman.

Bergman was described by Woody Allen as "the greatest film artist since the invention of the motion picture camera," and it is impossible to speak of film in Scandinavia without mentioning his name. Yet he is far from the only name in Swedish film - in fact, perhaps his greatest legacy is the throng of internationally acclaimed Swedish film directors active today.

A string of filmmaking success stories over the past couple of decades – including Thomas Alfredson, Lukas Moodysson, Josef Fares and Roy Andersson – all owe a lot to a man who has done as much to brand Sweden as Volvo, Abba and the Nobel Prize and whose name continues to inspire a thriving and diverse industry.

Bergman started making films in his childhood, and began working as a theatre director before moving onto film, first as a writer, with Frenzy in 1944. It would take him 11 years however, to receive his first international recognition for Smiles of a Summer Night in 1955.

It was more than just creative genius that turned the Swede into a household name though.

“Bergman was lucky in some ways - he became successful at just the right time,” says Maaret Koskinen, professor in film studies at Stockholm University - which in its former incarnation as Stockholm University College was Bergman's alma mater.

The first factor that helped Bergman succeed was the growth of film studies as an academic discipline.

"This was especially relevant at the end of the 50s with Seventh Seal, and Wild Strawberries, films that were food for thought and, more important perhaps, food for analysis," says Koskinen.

Bergman was also aided by the fact that his career coincided with the golden age of film criticism:

"Film critics had more sway on public opinion then than they do today," according to Koskinen.

A third helping hand came from a changing society:

"The sexual revolution was going on and in America particularly, the fight against censorship, both in books and films was in full swing," says Koskinen.

"The Silence helped chip away at the American censorship laws and push Bergman’s brand further. A tiny fraction of the film was censored, but it was enough to get authoritative voices like Norman Mailer jumping to his defence and, in doing so, solidifying his reputation."

But these three factors would have meant little if his work was not of exceptional quality in the first place.

Bergman had proved himself by creating artistic work, often wrapped up in existential angst, that would beguile and thrill both critics and the public. He picked up the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film for two consecutive years, with The Virgin Spring in 1960 and Through a Glass Darkly in 1961.

Fittingly, he won his third Academy Award in 1983 for the last feature film he made, Fanny and Alexander, a drama about an upper-middle class family, set in Uppsala in the 19th Century.

Little did he know at the time but 'Brand Bergman' was also paving the way for generations of his compatriots such as Mai Zetterling, Arne Mattson and Roy Andersson, who have gone on to make Sweden a country known as a home to great filmmaking.

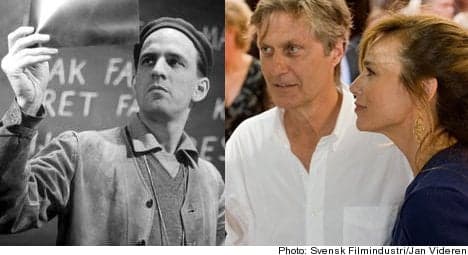

More recently Lasse Hallström (pictured above with wife Lena Olin, who starred in numerous Bergman films), won Oscar nominations for My Life as a Dog and The Cider House Rules and further success with What's Eating Gilbert Grape, Chocolat and Casanova.

But while Bergman has inspired many, his greatness has sometimes had a tendency to cast a shadow over everything and everyone coming out of Sweden’s film industry.

Certainly Fanny and Alexander had such a large budget that it left little money for other projects in the industry at the time, but Koskinen claims that the lack of high level success in the early eighties was more down to a lack of quality generally than simply finance. In any case, Sweden did at that time became known for some great documentary makers, like Stefan Jarl, she argues.

"Bergman aside, it is also critical that Sweden has been known traditionally as somewhere that offers high quality in terms of film workers. It is a stamp of quality to be from here," she says.

His reputation undoubtedly also helped the careers of some of the country’s most in-demand figures today. The films of the Stieg Larsson Millennium books - both the Swedish and English versions - have wowed audiences over the past few years. Another leading Swedish film director, is Tomas Alfredson, who scored a hit internationally with the offbeat romantic vampire film Let the Right One In and recently won similar acclaim for his remake of the classic Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

Ingmar Bergman’s films and Larsson’s books may differ in many ways, but the author is carrying on a tradition perhaps owing more to the director than anyone else, for bringing Sweden and its creativity to the attention of a larger global audience. What the country lacks in numbers, it more than makes up for in creativity and artistic productivity.

Stockholm University is one of the leading centres for cinema or film studies in Europe. Many courses are taught in English, including a Master's Programme in Cinema Studies.

Article sponsored by Stockholm University

This content was paid for by an advertiser and produced by The Local's Creative Studio.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.