Swedish green-burial firm to turn frozen corpses in compost

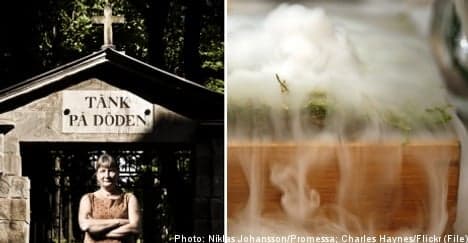

A posthumous bath in liquid nitrogen pioneered by an eco-minded Swedish entrepreneur may be the key to the world's first completely ecological burial alternative, the Local’s Karen Holst discovers.

The phrase ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’ has long been connected with burial services, having originated from the 17th century Book of Common Prayer.

But the idea of actually returning to the earth in an ecological manner that nourishes the soil is one that Swedish scientist Susanne Wiigh-Mäsak has sought to near-fruition across the span of a decade.

“We need to look at how we can take care of all organic material, including us. Our options today are definitely not appealing – slowly rotting in the soil or destroying the body by burning it in a way that is not gentle,” she says.

Terming the process ‘promession,’ Wiigh-Mäsak has worked tirelessly to bring this 100 percent ecological burial alternative to the wider world.

“Promession reshapes, dries and allows the body to be cared for by the soil. It offers a very natural connection with nature and a more appealing way to consider death.”

As she prepares to open the first ‘promator’ facility at the end of the year, Wiigh-Mäsak has received expressions of interest in the technology from more than 60 countries, including Vietnam, the United Kingdom, South Africa, the Netherlands, Canada and the United States.

Having a near life-long affection for protecting the planet, the 54-year-old ecologist and biologist worked in a chemical plant for 15 years with the ambition of affecting change from ‘the inside.’

Parallel to her career, Wiigh-Mäsak, a resident of the remote island of Lyr, about 80 kilometres off the shores of Gothenburg, began an organic gardening business.

“On the island, we grow our own food, our own vegetables, we sell potatoes and I quickly realized that there was too little knowledge about how to make a really good compost,” Wiigh-Mäsak says.

Taking it upon herself, she developed a way to construct compost ‘how nature intended’ and describes it as clean and effective. This method gained popularity and even earned her an award from the King of Sweden for her business innovation.

“Later I got to thinking – we are almost seven billion people on the planet and in the next one hundred years we will all die – everyone will either rot or burn – and I did not find that acceptable,” she recalls.

“I decided that when I die, I would like to be composted and I kept thinking about how it could be done the way nature intended – to return to the same system from which we originated.”

In 1997, Wiigh-Mäsak established the company Promessa Organic, inspired by the Italian word promessa meaning oath or truth.

It is founded on the firm belief that a body can be returned to the ecological cycle in a dignified manner as a valuable contribution to the living earth.

At its most basic explanation, it involves recycling human bodies as fertilizer, a process based on preserving the body in a biological form after death and returning it to the soil.

The first step of promession is to remove the approximate 70-percent water component from the corpse.

Within a week and a half after death, the body is frozen to -18 degrees Celsius and then submerged in liquid nitrogen, a substance that Promessa Organic claims does not cause any environmental harm.

The body now very brittle is then treated to vibrations of specific amplitude that reduce the corpse to a fine organic powder, both hygienic and odourless. It finally is laid in a biodegradable container made of cornstarch.

“The remains are buried in a shallow grave and the living soil turns it into compost in about six to twelve months,” says Wiigh-Mäsak, who recommends planting a tree or rosebush next to the grave as a symbol of the deceased, knowing that the composted soil will support the plant’s life.

“It’s a beautiful and more joyful way to understand where the body has gone,” she says.

The entire promession is a closed and individual process, meaning that once the body is placed in the machine, or prometor, human hands do not handle the remains again.

To date, promession has been tested on the carcasses of hundreds of naturally expired pigs and cows. Wiigh-Mäsak planted roses above the containers and proclaims ‘excellent results.’

While today’s most common burial alternatives are either a casket laid in the ground or cremation, Wiigh-Mäsak contends that people need to begin thinking about the environmental impact of those choices.

“Most people don’t know what organic truly means. It refers to matter that contains carbon and not all organic material is environmentally friendly, like gas and oil,” the scientist turned entrepreneur says of the common misgiving that cremation is a more environmentally-friendly process.

While it takes between two to four hours for a body to be cremated at about 815 to 1,000 degrees Celsius, the process also burns fossil fuels and releases pollutants into the air.

According to reports, cremation can use up to 23 litres of fluid oil and 0.5 kilograms of activated carbon.

In Sweden, cremation alone accounts for an annual contribution of one third of the nation’s total mercury emissions, according to the ecological burial company.

Adding to its overall environmental impact, cremation’s surging popularity spurred an entire market of creative options for commemorating the remains, such as sending the ashes into eternal space orbit, using the remains in a commissioned painting or other piece of art, and even turning the ashes into diamonds, wind chimes, birdbaths, motorcycle gas tanks and fireworks.

The casket route apparently fairs no better.

It takes an entire full-grown tree to make a traditional casket and burials require that a corpse be filled with embalming fluids.

These fluids can pollute the ground water during the 20-100 year span of a body’s decaying process.

“Rotting is a slow, ugly, smelly process. Nature intended that we go back to the same system that we originated from and now we can become a gift to the soil instead of a being problem,” Wiigh-Mäsak says of promession.

Her critics renounce the idea of the ecological burial, often referring to it as outrageous, unrealistic or intangible.

“This method does not exist in the world, it is only a paper product, just an idea and it is a pity that is has been written that it exists,” states a spokesperson from Fonus, Sweden’s nationwide and most-used funerary service company.

Wiigh-Mäsak maintains the reality of promession is close at hand and points out that an ecological burial is included as a lawful and accepted burial alternative in the Church of Sweden’s official burial guide.

In fact, Promessa Organic currently has 12 bodies waiting in the freezing room.

“My wife chose this type of burial because it integrates the body into the ecological system immediately,” says Folke Günther, who’s wife, Jane, lost her life to illness two years ago and chose an ecological burial.

He says that while the wait has not been unexpected, neither has it been difficult.

He is “totally supportive” of his wife's choice, so much so that he has declared the same choice for his own passing.

“For now, I just look forward to getting it (promession) here and finishing the process,” says Günther, who will plant Jane’s favourite tree near the burial of her remains at a church in Lund.

And hopefully it won’t be too much longer.

While the specific location of the country’s first promatoria is not yet finalized, it is slated to open in December 2011.

Comments

See Also

The phrase ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’ has long been connected with burial services, having originated from the 17th century Book of Common Prayer.

But the idea of actually returning to the earth in an ecological manner that nourishes the soil is one that Swedish scientist Susanne Wiigh-Mäsak has sought to near-fruition across the span of a decade.

“We need to look at how we can take care of all organic material, including us. Our options today are definitely not appealing – slowly rotting in the soil or destroying the body by burning it in a way that is not gentle,” she says.

Terming the process ‘promession,’ Wiigh-Mäsak has worked tirelessly to bring this 100 percent ecological burial alternative to the wider world.

“Promession reshapes, dries and allows the body to be cared for by the soil. It offers a very natural connection with nature and a more appealing way to consider death.”

As she prepares to open the first ‘promator’ facility at the end of the year, Wiigh-Mäsak has received expressions of interest in the technology from more than 60 countries, including Vietnam, the United Kingdom, South Africa, the Netherlands, Canada and the United States.

Having a near life-long affection for protecting the planet, the 54-year-old ecologist and biologist worked in a chemical plant for 15 years with the ambition of affecting change from ‘the inside.’

Parallel to her career, Wiigh-Mäsak, a resident of the remote island of Lyr, about 80 kilometres off the shores of Gothenburg, began an organic gardening business.

“On the island, we grow our own food, our own vegetables, we sell potatoes and I quickly realized that there was too little knowledge about how to make a really good compost,” Wiigh-Mäsak says.

Taking it upon herself, she developed a way to construct compost ‘how nature intended’ and describes it as clean and effective. This method gained popularity and even earned her an award from the King of Sweden for her business innovation.

“Later I got to thinking – we are almost seven billion people on the planet and in the next one hundred years we will all die – everyone will either rot or burn – and I did not find that acceptable,” she recalls.

“I decided that when I die, I would like to be composted and I kept thinking about how it could be done the way nature intended – to return to the same system from which we originated.”

In 1997, Wiigh-Mäsak established the company Promessa Organic, inspired by the Italian word promessa meaning oath or truth.

It is founded on the firm belief that a body can be returned to the ecological cycle in a dignified manner as a valuable contribution to the living earth.

At its most basic explanation, it involves recycling human bodies as fertilizer, a process based on preserving the body in a biological form after death and returning it to the soil.

The first step of promession is to remove the approximate 70-percent water component from the corpse.

Within a week and a half after death, the body is frozen to -18 degrees Celsius and then submerged in liquid nitrogen, a substance that Promessa Organic claims does not cause any environmental harm.

The body now very brittle is then treated to vibrations of specific amplitude that reduce the corpse to a fine organic powder, both hygienic and odourless. It finally is laid in a biodegradable container made of cornstarch.

“The remains are buried in a shallow grave and the living soil turns it into compost in about six to twelve months,” says Wiigh-Mäsak, who recommends planting a tree or rosebush next to the grave as a symbol of the deceased, knowing that the composted soil will support the plant’s life.

“It’s a beautiful and more joyful way to understand where the body has gone,” she says.

The entire promession is a closed and individual process, meaning that once the body is placed in the machine, or prometor, human hands do not handle the remains again.

To date, promession has been tested on the carcasses of hundreds of naturally expired pigs and cows. Wiigh-Mäsak planted roses above the containers and proclaims ‘excellent results.’

While today’s most common burial alternatives are either a casket laid in the ground or cremation, Wiigh-Mäsak contends that people need to begin thinking about the environmental impact of those choices.

“Most people don’t know what organic truly means. It refers to matter that contains carbon and not all organic material is environmentally friendly, like gas and oil,” the scientist turned entrepreneur says of the common misgiving that cremation is a more environmentally-friendly process.

While it takes between two to four hours for a body to be cremated at about 815 to 1,000 degrees Celsius, the process also burns fossil fuels and releases pollutants into the air.

According to reports, cremation can use up to 23 litres of fluid oil and 0.5 kilograms of activated carbon.

In Sweden, cremation alone accounts for an annual contribution of one third of the nation’s total mercury emissions, according to the ecological burial company.

Adding to its overall environmental impact, cremation’s surging popularity spurred an entire market of creative options for commemorating the remains, such as sending the ashes into eternal space orbit, using the remains in a commissioned painting or other piece of art, and even turning the ashes into diamonds, wind chimes, birdbaths, motorcycle gas tanks and fireworks.

The casket route apparently fairs no better.

It takes an entire full-grown tree to make a traditional casket and burials require that a corpse be filled with embalming fluids.

These fluids can pollute the ground water during the 20-100 year span of a body’s decaying process.

“Rotting is a slow, ugly, smelly process. Nature intended that we go back to the same system that we originated from and now we can become a gift to the soil instead of a being problem,” Wiigh-Mäsak says of promession.

Her critics renounce the idea of the ecological burial, often referring to it as outrageous, unrealistic or intangible.

“This method does not exist in the world, it is only a paper product, just an idea and it is a pity that is has been written that it exists,” states a spokesperson from Fonus, Sweden’s nationwide and most-used funerary service company.

Wiigh-Mäsak maintains the reality of promession is close at hand and points out that an ecological burial is included as a lawful and accepted burial alternative in the Church of Sweden’s official burial guide.

In fact, Promessa Organic currently has 12 bodies waiting in the freezing room.

“My wife chose this type of burial because it integrates the body into the ecological system immediately,” says Folke Günther, who’s wife, Jane, lost her life to illness two years ago and chose an ecological burial.

He says that while the wait has not been unexpected, neither has it been difficult.

He is “totally supportive” of his wife's choice, so much so that he has declared the same choice for his own passing.

“For now, I just look forward to getting it (promession) here and finishing the process,” says Günther, who will plant Jane’s favourite tree near the burial of her remains at a church in Lund.

And hopefully it won’t be too much longer.

While the specific location of the country’s first promatoria is not yet finalized, it is slated to open in December 2011.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.