John E. Woods: Bringing German literature to the world

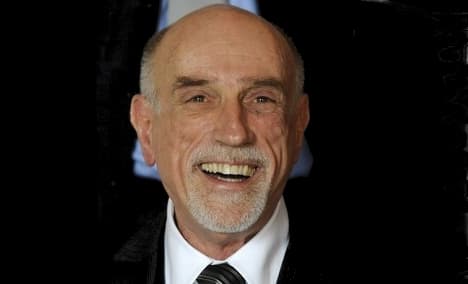

Prize-winning translator John E. Woods has brought great German literature to English speakers for more than 30 years. The Local's series "Making it in Germany" sat down with him to discuss what he calls a dangerous and lonely task.

Literary translators don’t get much respect. They fight to get their names on book jackets and often scrape by on meagre fees that bitterly belie their labour of love.

But not John E. Woods. For more than three decades, the Indianapolis-born translator has not only made it possible for English speakers to read some of Germany’s greatest works of fiction, he’s managed to make a living and a name for himself in what is usually an anonymous endeavour.

Though he’s had plenty of success, Woods says his is a lonely profession that shouldn’t even exist.

“It’s dangerous and it should not be allowed. I’m serious,” he told The Local over tea at his favourite neighbourhood cafe in Berlin. “Any translator worth his or her salt knows precisely how impossible it is, but it’s there. It calls out to be done and has been done since the very beginning.”

Without translators, the dapper 67-year-old says, there would be no world literature, but the personal nature of literary expression means that avoiding some parts of the work being “lost in translation,” as the adage goes, is impossible.

What can be salvaged is just a shadow of the original, Woods said.

“If you’re working with serious authors, there are five resonances, whether what you hear is the echo of Goethe’s Faust, or that flashy, nasty Berlin German that I love, there’s all these levels happening in any good text,” he said.

On a good day translators can preserve two out of five of these “resonances,” Woods explained.

His metaphor: “Here the author has created a beautiful meadow with a cow, a landscape worthy of a Dutch master, and what I give you is a very good steak.”

Publishers must find Woods’ word-steak tasty, because over the years he has been contracted to translate some of the German-language's greatest literary works.

A living legend

Since coming to Germany to study theology, and marrying his Goethe Institute language course teacher, Woods has Anglicized the words of Arno Schmidt, Thomas Mann, Patrick Süskind, Döblin, Raabe, Dürrenmatt, Grass, Ransmayr, Dörrie, Treichel and others.

Katy Derbyshire, a Berlin-based translator currently tackling the überhyped novel “Axolotl Roadkill,” by controversial teen author Helene Hegemann, told The Local that Woods is a “living legend” in the field.

“He’s one of the few that people who know about international literature would know,” she said. “If you’re the kind of person who would notice a translator’s name – which is few and far between because we are always a step behind the writer – then John will be a big name up there in lights.”

But his career started with a “fluke,” Woods said.

In 1976, he was an aspiring novelist “getting nowhere” when he began reading a copy of German author Arno Schmidt’s book Abend mit Goldrand, which many had considered untranslatable up until that point.

“He is, for lack of a better handle, the German James Joyce - really complicated meta fiction,” Woods said. “Instead of staring at the wall with writer’s block, I said, ‘Ok, I’m going to translate this.’ And the snowball got rolling.”

After it was published under the English title “Evening Edged in Gold,” in 1980, Woods was awarded his first PEN Prize for translation.

He went on to win a second PEN in 1987 for Süskind’s “Perfume: The Story of a Murderer,” which director Tom Tykwer turned into a feature film in 2006. Then in 2008, Woods was awarded the prestigious Goethe Medal for his enormous body of work in a role the institute characterised as a “cultural mediator.”

“It’s not that I’m the most accomplished translator of German into English, I can name 10 people at least as good if not better, but I hit it right,” he told The Local.

With the first Schmidt translation, Woods hit the professional equivalent of a bull’s eye when he came to the attention of Helen Wollf, the widow of innovative German publisher Kurt Wolff, a woman that Woods described as the “Grande dame” of translated European literature. The couple had made their big break in English-language publishing with translations of German-language authors Karl Jaspers, Walter Benjamin, Günter Grass, Max Frisch, and other European greats.

Wolff made sure the first translation was published and helped form other contacts that led to the Süskind job and many others, including exclusive contracts to translate Thomas Mann and Arno Schmidt works.

“I’ve gotten respect and I’ve also made a living at it, and I may be one of the only translators I know who isn’t also a professor somewhere or working another job,” Woods said, explaining that his unusual contracts led to not having to “hustle” his work, which left time to actually get it done.

His favourite translation has been Thomas Mann’s “Joseph and His Brothers.”

“It’s the most beautiful thing Mann ever did, his ‘Divine Comedy,’ it’s spectacular,” he said, describing the challenges of working through an ending that was so sublime he shed tears over his keyboard.

Thankless work

Meanwhile other translators of Woods’ acquaintance are struggling. The VdÜ association for Germany's literary translators, an organisation fighting for better compensation for those in the sector, recently reported that many “successful and busy” translators earn an income of between €13,000 and €14,000 per year, which is below the poverty line.

And though world literature would not exist without translators, those who manage to get their work noticed by a wider audience are generally overlooked by critics.

“Usually it’s the one-adverb review, ‘marvellously’ translated versus ‘stodgily’ translated,” Woods said.

“Then you get a discussion of this author’s marvellous prose, and of course that was his prose. But it’s what the translators do with our mother tongue that makes that book either sing or end up as a dreary puddle on the floor.”

Another difficulty is a relative lack of interest in foreign literature in the English-speaking world.

The German Book Office reports that compared to the more than 50,000 foreign titles published in Germany each year, only about 3,000 German books make it into translation worldwide. Of these, fewer than 40 works of fiction are translated into English each year, Woods estimated.

For three decades Woods’ award-winning work has often topped this short list, but not for much longer. He plans to retire within a year after finishing Arno Schmidt’s 1,330-page opus, Zettel’s Traum, which will be titled “Bottom’s Dream,” in English.

“When I’m done with ‘Bottom’s Dream,’ I’ve done my work,” he said. “I plan to enjoy Berlin. I love this city. It sparkles for me.”

Know someone who's "made it" in Germany? Email us at: [email protected]

Comments

See Also

Literary translators don’t get much respect. They fight to get their names on book jackets and often scrape by on meagre fees that bitterly belie their labour of love.

But not John E. Woods. For more than three decades, the Indianapolis-born translator has not only made it possible for English speakers to read some of Germany’s greatest works of fiction, he’s managed to make a living and a name for himself in what is usually an anonymous endeavour.

Though he’s had plenty of success, Woods says his is a lonely profession that shouldn’t even exist.

“It’s dangerous and it should not be allowed. I’m serious,” he told The Local over tea at his favourite neighbourhood cafe in Berlin. “Any translator worth his or her salt knows precisely how impossible it is, but it’s there. It calls out to be done and has been done since the very beginning.”

Without translators, the dapper 67-year-old says, there would be no world literature, but the personal nature of literary expression means that avoiding some parts of the work being “lost in translation,” as the adage goes, is impossible.

What can be salvaged is just a shadow of the original, Woods said.

“If you’re working with serious authors, there are five resonances, whether what you hear is the echo of Goethe’s Faust, or that flashy, nasty Berlin German that I love, there’s all these levels happening in any good text,” he said.

On a good day translators can preserve two out of five of these “resonances,” Woods explained.

His metaphor: “Here the author has created a beautiful meadow with a cow, a landscape worthy of a Dutch master, and what I give you is a very good steak.”

Publishers must find Woods’ word-steak tasty, because over the years he has been contracted to translate some of the German-language's greatest literary works.

A living legend

Since coming to Germany to study theology, and marrying his Goethe Institute language course teacher, Woods has Anglicized the words of Arno Schmidt, Thomas Mann, Patrick Süskind, Döblin, Raabe, Dürrenmatt, Grass, Ransmayr, Dörrie, Treichel and others.

Katy Derbyshire, a Berlin-based translator currently tackling the überhyped novel “Axolotl Roadkill,” by controversial teen author Helene Hegemann, told The Local that Woods is a “living legend” in the field.

“He’s one of the few that people who know about international literature would know,” she said. “If you’re the kind of person who would notice a translator’s name – which is few and far between because we are always a step behind the writer – then John will be a big name up there in lights.”

But his career started with a “fluke,” Woods said.

In 1976, he was an aspiring novelist “getting nowhere” when he began reading a copy of German author Arno Schmidt’s book Abend mit Goldrand, which many had considered untranslatable up until that point.

“He is, for lack of a better handle, the German James Joyce - really complicated meta fiction,” Woods said. “Instead of staring at the wall with writer’s block, I said, ‘Ok, I’m going to translate this.’ And the snowball got rolling.”

After it was published under the English title “Evening Edged in Gold,” in 1980, Woods was awarded his first PEN Prize for translation.

He went on to win a second PEN in 1987 for Süskind’s “Perfume: The Story of a Murderer,” which director Tom Tykwer turned into a feature film in 2006. Then in 2008, Woods was awarded the prestigious Goethe Medal for his enormous body of work in a role the institute characterised as a “cultural mediator.”

“It’s not that I’m the most accomplished translator of German into English, I can name 10 people at least as good if not better, but I hit it right,” he told The Local.

With the first Schmidt translation, Woods hit the professional equivalent of a bull’s eye when he came to the attention of Helen Wollf, the widow of innovative German publisher Kurt Wolff, a woman that Woods described as the “Grande dame” of translated European literature. The couple had made their big break in English-language publishing with translations of German-language authors Karl Jaspers, Walter Benjamin, Günter Grass, Max Frisch, and other European greats.

Wolff made sure the first translation was published and helped form other contacts that led to the Süskind job and many others, including exclusive contracts to translate Thomas Mann and Arno Schmidt works.

“I’ve gotten respect and I’ve also made a living at it, and I may be one of the only translators I know who isn’t also a professor somewhere or working another job,” Woods said, explaining that his unusual contracts led to not having to “hustle” his work, which left time to actually get it done.

His favourite translation has been Thomas Mann’s “Joseph and His Brothers.”

“It’s the most beautiful thing Mann ever did, his ‘Divine Comedy,’ it’s spectacular,” he said, describing the challenges of working through an ending that was so sublime he shed tears over his keyboard.

Thankless work

Meanwhile other translators of Woods’ acquaintance are struggling. The VdÜ association for Germany's literary translators, an organisation fighting for better compensation for those in the sector, recently reported that many “successful and busy” translators earn an income of between €13,000 and €14,000 per year, which is below the poverty line.

And though world literature would not exist without translators, those who manage to get their work noticed by a wider audience are generally overlooked by critics.

“Usually it’s the one-adverb review, ‘marvellously’ translated versus ‘stodgily’ translated,” Woods said.

“Then you get a discussion of this author’s marvellous prose, and of course that was his prose. But it’s what the translators do with our mother tongue that makes that book either sing or end up as a dreary puddle on the floor.”

Another difficulty is a relative lack of interest in foreign literature in the English-speaking world.

The German Book Office reports that compared to the more than 50,000 foreign titles published in Germany each year, only about 3,000 German books make it into translation worldwide. Of these, fewer than 40 works of fiction are translated into English each year, Woods estimated.

For three decades Woods’ award-winning work has often topped this short list, but not for much longer. He plans to retire within a year after finishing Arno Schmidt’s 1,330-page opus, Zettel’s Traum, which will be titled “Bottom’s Dream,” in English.

“When I’m done with ‘Bottom’s Dream,’ I’ve done my work,” he said. “I plan to enjoy Berlin. I love this city. It sparkles for me.”

Know someone who's "made it" in Germany? Email us at: [email protected]

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.