'He was a part of the team at the Sobibor'

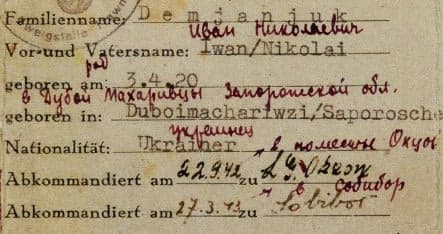

The likely trial of Nazi death camp guard John Demjanjuk may be one of the last times anyone is prosecuted for crimes committed during World War II.

Demjanjuk's extradition to Germany this week has sparked a new debate about whether the country has done enough to come to terms with and make restitution for its past. The Local spoke with Prof. Helgard Kramer, a specialist in cultural sociology and historical anthropology at Berlin’s Free University.

Hasn’t Germany come to terms with its past?

The confrontation with the country’s past picked up steam with the trial of [SS architect of the Holocaust Adolf] Eichmann in Jerusalem and the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials in 1963. Every generation has then had a new and different debate about it, like when Schindler’s List came out or [Daniel] Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Or even with the Wehrmacht exhibition about the crimes of the normal army. Right after the war there was silence but that changed in the 1960s and we’ve made good progress. In the 1980s, for example, a lot of memorials began cropping up.

Is this the right way to work through it?

It’s a past for which you can never get closure. And that isn’t even something to work toward. It’s a very difficult thing. It is one thing to learn about the Holocaust but it’s entirely different when it becomes personal. It’s hard to rectify your feelings for your grandparents and what you’ve learned about National Socialism and what some of them may have done. You always idealise your own family. The people who migrate here have a different view of the past but their children – the second and third generations – end up taking on the guilt as well.

What about Demjanjuk’s defence that he was forced to become a guard for the Nazis? It sounds almost plausible.

It’s been confirmed that he was a part of the team at the Sobibor [death camp]. In order for someone to be tried for murder in Germany you have to connect them to at least one death. The Nazis were very diligent record keepers and they can prove who died there while he worked there. The eyewitnesses don’t remember him but they have said that the Travniki guards there were very anti-Semitic and often used an extra dollop of sadism. Also he never took any opportunity to get away from the camp like some of his colleagues, albeit at a certain risk. If he never talks you’ll never be able to prove he was one of the more sadistic ones but he was there and he didn’t try to get away.

Even if they find other potential war criminals, they’re all getting very old. Will they be able to stand trial?

At their age it’s hard to say if they’ll be able to stand trial. The health of these criminals has a long history. So many cases in the ‘60s and ‘70s failed because they were able to get friendly doctors to testify that they were unfit for trial. These doctors were sometimes former Nazi doctors but their testimony was hard to contest. They would coach the criminals on how to feign various illnesses.

What else should Germany be doing to deal with this chapter of its history?

We have to ensure that the memories and confrontation take other forms. The conflict has to remain alive. There are a number of good initiatives. The Holocaust Memorial in Berlin turned out very well and the cobblestone project here in Berlin [that places brass cobblestones with victims’ names in front of their former houses] is also a good thing.

Comments

See Also

Demjanjuk's extradition to Germany this week has sparked a new debate about whether the country has done enough to come to terms with and make restitution for its past. The Local spoke with Prof. Helgard Kramer, a specialist in cultural sociology and historical anthropology at Berlin’s Free University.

Hasn’t Germany come to terms with its past?

The confrontation with the country’s past picked up steam with the trial of [SS architect of the Holocaust Adolf] Eichmann in Jerusalem and the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials in 1963. Every generation has then had a new and different debate about it, like when Schindler’s List came out or [Daniel] Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Or even with the Wehrmacht exhibition about the crimes of the normal army. Right after the war there was silence but that changed in the 1960s and we’ve made good progress. In the 1980s, for example, a lot of memorials began cropping up.

Is this the right way to work through it?

It’s a past for which you can never get closure. And that isn’t even something to work toward. It’s a very difficult thing. It is one thing to learn about the Holocaust but it’s entirely different when it becomes personal. It’s hard to rectify your feelings for your grandparents and what you’ve learned about National Socialism and what some of them may have done. You always idealise your own family. The people who migrate here have a different view of the past but their children – the second and third generations – end up taking on the guilt as well.

What about Demjanjuk’s defence that he was forced to become a guard for the Nazis? It sounds almost plausible.

It’s been confirmed that he was a part of the team at the Sobibor [death camp]. In order for someone to be tried for murder in Germany you have to connect them to at least one death. The Nazis were very diligent record keepers and they can prove who died there while he worked there. The eyewitnesses don’t remember him but they have said that the Travniki guards there were very anti-Semitic and often used an extra dollop of sadism. Also he never took any opportunity to get away from the camp like some of his colleagues, albeit at a certain risk. If he never talks you’ll never be able to prove he was one of the more sadistic ones but he was there and he didn’t try to get away.

Even if they find other potential war criminals, they’re all getting very old. Will they be able to stand trial?

At their age it’s hard to say if they’ll be able to stand trial. The health of these criminals has a long history. So many cases in the ‘60s and ‘70s failed because they were able to get friendly doctors to testify that they were unfit for trial. These doctors were sometimes former Nazi doctors but their testimony was hard to contest. They would coach the criminals on how to feign various illnesses.

What else should Germany be doing to deal with this chapter of its history?

We have to ensure that the memories and confrontation take other forms. The conflict has to remain alive. There are a number of good initiatives. The Holocaust Memorial in Berlin turned out very well and the cobblestone project here in Berlin [that places brass cobblestones with victims’ names in front of their former houses] is also a good thing.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.