Happy birthday Heiner Müller

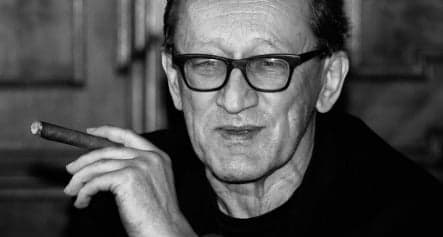

The eastern German dramatist Heiner Müller was born eighty years ago on Friday. As the cultural establishment salutes his legend, Daniel Miller questions his legacy.

“Who is the corpse in the hearse about whom there's such a hue and cry?” asks a character in Heiner Müller's most famous play Hamletmachine.

The answer in this case is Heiner Müller himself.

Eighty years after his birth, Germany on Friday celebrates the deceased dramatist's life and legacy. In Berlin, the Arts Academy is holding two days of commemorations featuring cultural luminaries like Peter Weibel, Austrian Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek, and leftist politician Gregor Gysi.

Across the town, the Brecht Literature Forum will be hosting their own, smaller-scale reading in Brecht's former residence. Meanwhile in Hesse, the Schauspiel Frankfurt has programmed a three-day series of lectures and discussions, entitled “Experience with Heiner Müller,” in cooperation with the city's Johann Wolfgang Goethe University.

Müller himself would probably have felt ambivalent about all this festivity. “I owe the world a dead person,” Müller mused late in life to Alexander Kluge. “The state takes possession of the dead.” He would turn out to be more right than he realized.

In Müller's lifetime, the author achieved the rare feat of winning all the major literary prizes of both East and West Germany, picking up both the Mülheim and Büchner prizes of the democratic west, as well as the Heinrich Mann and National prizes of the communist east.

Thirteen years after his death from cancer, his reputation remains enormous. In 1998, the journal New German Critique devoted a special issue to his work. He is still the only playwright to have ever received such an honour. More recently, the powerhouse intellectual Frankfurt publishing house Suhrkamp last month issued a twelve-volume, doorstopper edition of Mueller's collected works.

The only twentieth century German dramatist who holds the same status is Bertolt Brecht. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Müller had a complicated relationship with the man he succeeded as director of the Berliner Ensemble.

Both authors were poets, theorists and public intellectuals, as well as men of the theatre. Both shared a commitment to socialism, and a taste for cigars. Both lived through tumultuous periods of German history, and both treated historical themes at length in their work.

Yet Müller was his own man artistically, and he remained consistently wary of Brecht's powerful influence. “To use Brecht without criticizing him,” he once wrote, “is treason.”

Based on this understanding, Müller developed a remarkably different style of theatre to his great predecessor. His was a free-wheeling, densely poetic strategy which upheld a logic of associations, rather than a logic of linear plot.

In Hamletmachine, this strategy drove Müller to borrow interchangeably from Shakespeare, T.S, Eliot, Jean-Luc Godard, and Manson Family member Susan Atkins. A terrorist quotation from Atkins, spoken by an updated Ophelia modelled after Ulrike Meinhof, closes the play: “When she walks through your bedroom with butcher knives, then you'll know the truth.”

“Theatre,” claimed Müller, “is a laboratory for the social imagination.” But the playwright ultimately ended up disappointed with the course that the German social imagination took.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Müller abrasively opposed reunification, accusing West Germany of “moral complacency.” He warned in the New York Times of a “resurgence of nationalism, racism and anti-Semitism” and that “a reunited Germany will make life unpleasant for its neighbours.”

Such as a stance was typical of Müller, who divided his time in the 1990s between writing poetry and appearing on talk shows, swirling ice cubes around in drained glasses of whiskey while offering dark, nihilistic pronouncements. But this abrasive aspect of his personality was tended to be downplayed in recent years, as his canonization has gathered pace.

“On stage,” Müller claimed, “you need an enemy. German history is my enemy, and I want to stare into the white of its eye.” But Müller has now become part of German history, leaving his legacy in a strange position indeed.

Comments

See Also

“Who is the corpse in the hearse about whom there's such a hue and cry?” asks a character in Heiner Müller's most famous play Hamletmachine.

The answer in this case is Heiner Müller himself.

Eighty years after his birth, Germany on Friday celebrates the deceased dramatist's life and legacy. In Berlin, the Arts Academy is holding two days of commemorations featuring cultural luminaries like Peter Weibel, Austrian Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek, and leftist politician Gregor Gysi.

Across the town, the Brecht Literature Forum will be hosting their own, smaller-scale reading in Brecht's former residence. Meanwhile in Hesse, the Schauspiel Frankfurt has programmed a three-day series of lectures and discussions, entitled “Experience with Heiner Müller,” in cooperation with the city's Johann Wolfgang Goethe University.

Müller himself would probably have felt ambivalent about all this festivity. “I owe the world a dead person,” Müller mused late in life to Alexander Kluge. “The state takes possession of the dead.” He would turn out to be more right than he realized.

In Müller's lifetime, the author achieved the rare feat of winning all the major literary prizes of both East and West Germany, picking up both the Mülheim and Büchner prizes of the democratic west, as well as the Heinrich Mann and National prizes of the communist east.

Thirteen years after his death from cancer, his reputation remains enormous. In 1998, the journal New German Critique devoted a special issue to his work. He is still the only playwright to have ever received such an honour. More recently, the powerhouse intellectual Frankfurt publishing house Suhrkamp last month issued a twelve-volume, doorstopper edition of Mueller's collected works.

The only twentieth century German dramatist who holds the same status is Bertolt Brecht. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Müller had a complicated relationship with the man he succeeded as director of the Berliner Ensemble.

Both authors were poets, theorists and public intellectuals, as well as men of the theatre. Both shared a commitment to socialism, and a taste for cigars. Both lived through tumultuous periods of German history, and both treated historical themes at length in their work.

Yet Müller was his own man artistically, and he remained consistently wary of Brecht's powerful influence. “To use Brecht without criticizing him,” he once wrote, “is treason.”

Based on this understanding, Müller developed a remarkably different style of theatre to his great predecessor. His was a free-wheeling, densely poetic strategy which upheld a logic of associations, rather than a logic of linear plot.

In Hamletmachine, this strategy drove Müller to borrow interchangeably from Shakespeare, T.S, Eliot, Jean-Luc Godard, and Manson Family member Susan Atkins. A terrorist quotation from Atkins, spoken by an updated Ophelia modelled after Ulrike Meinhof, closes the play: “When she walks through your bedroom with butcher knives, then you'll know the truth.”

“Theatre,” claimed Müller, “is a laboratory for the social imagination.” But the playwright ultimately ended up disappointed with the course that the German social imagination took.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Müller abrasively opposed reunification, accusing West Germany of “moral complacency.” He warned in the New York Times of a “resurgence of nationalism, racism and anti-Semitism” and that “a reunited Germany will make life unpleasant for its neighbours.”

Such as a stance was typical of Müller, who divided his time in the 1990s between writing poetry and appearing on talk shows, swirling ice cubes around in drained glasses of whiskey while offering dark, nihilistic pronouncements. But this abrasive aspect of his personality was tended to be downplayed in recent years, as his canonization has gathered pace.

“On stage,” Müller claimed, “you need an enemy. German history is my enemy, and I want to stare into the white of its eye.” But Müller has now become part of German history, leaving his legacy in a strange position indeed.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.